“If you could have dinner with anyone, dead or alive, who would you choose?”

When people are asked this question, many choose historical figures, and those are intriguing options. But for me, my number one pick would be my great-grandmother, Sylvia. She died two years before I was born, and she is the relative I most wish I knew now.

I know very little about her personality or what people thought of her. I also don’t know her hobbies or her likes and dislikes. I see that she was married multiple times, and her first husband was my great-grandfather. She may have loved him immensely, or he may have caused her great sorrow. Or both could be true at the same time.

Though much is unknown about her personally, I know she must have been immensely resilient. That’s because I know her story.

Without her, and without this story I’m about to tell you, I wouldn’t be here. In an obvious way, this is true about all of our relatives. But it’s also true because of the resilience and resolve she seemed to have in abundance. I wouldn’t be here if she hadn’t taken clandestine efforts to save her family and mine.

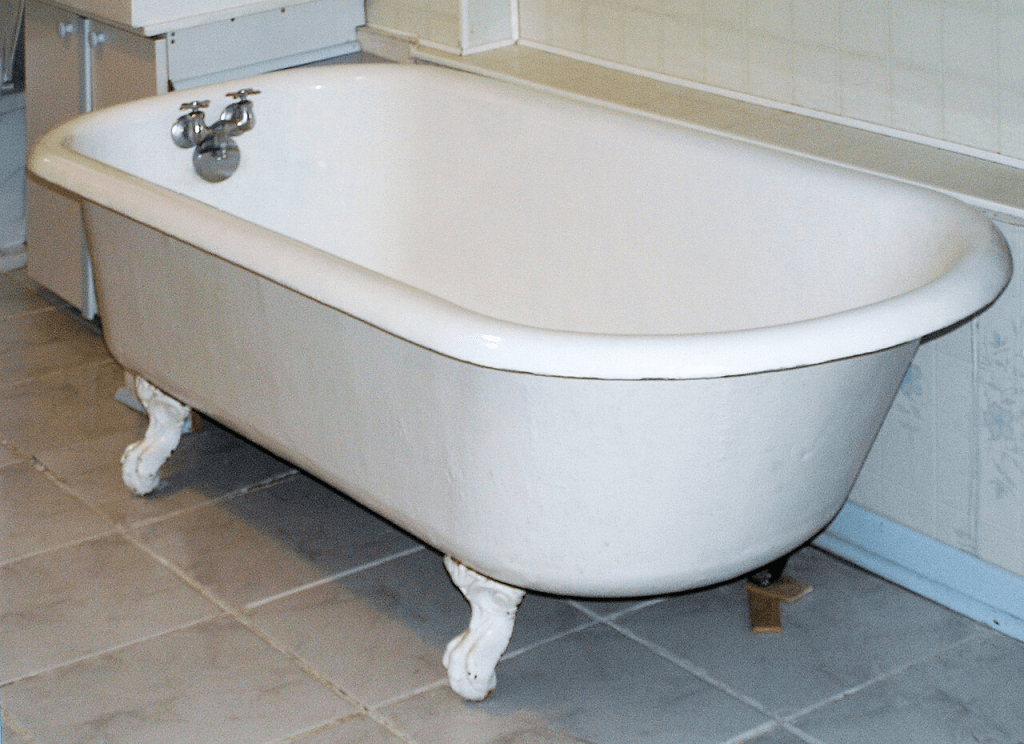

I am born of bathtub gin.

Here is how that took place:

In the aftermath of World War I, in the 1920s and the start of 1930s, my great-grandfather drank himself to death. This was the era of Prohibition. My grandmother, Sylvia’s daughter-in-law, told me that he would drink any alcohol he could get his hands on, even wood alcohol or ethanol. And so, tragically, and likely in a lot of pain (Maybe from the war? That’s my curiosity, but I don’t know), he died, not very long after Sylvia had given birth to her fifth baby.

And that fifth and youngest baby was my grandfather Jim. Suddenly, she had five mouths to feed and was newly a widow. Likely, the family was already poor, but in 1929, the very week Jim was born, the stock market crashed, too. The nation was plunged into the Great Depression.

I’ve heard this next part two different ways:

— At this point, recognizing she did not have the means to care well for her children, she placed them in a Catholic orphanage.

Or

–At this point, she began her secret business to care for her family, but she got caught, and her children were taken away and placed in a Catholic orphanage.

Whichever happened, I know what she did in the aftermath. My great-grandmother Sylvia became a moonshiner. She began to make bathtub gin and sell it illegally. She did this for years. And when she had enough money, she got her eldest child out of the orphanage. That child began to help her until they had enough money to get the second child out of the orphanage. And then they each helped, one by one, until she received all of her children back into her household.

Jim, my grandfather, lived in the orphanage the longest, until he was 7 years old. It was a remarkably difficult childhood. He told stories about how each Christmas, they brought toys down from the attic to give them as gifts to the kids. But then they would put them back in that attic, only to turn around and give them again the next Christmas. Once, he found a candy bar wrapper with the chocolate already eaten. He kept it just so he could smell it. These experiences must have been deeply traumatic for all of Sylvia’s children.

I would say that the death of their father and their difficult upbringing in a Catholic orphanage were the central generational traumas in my family. I can see unique ways that these have shaped us.

All that being said, alongside generational trauma, which we often inherit and work to heal, might we also inherit generational resilience? If so, do I receive that from Sylvia?

If that is true, it may help explain why many people have told me that I, too, am resilient.

I am born of bathtub gin.

Alongside the approximate 12.5% DNA I share with Sylvia, I hope that some of her resolve has come to me and my family, and perhaps through her, to people I know and love as well, even if they don’t share that DNA.

Last month, I visited my hometown, and at one point, I realized I was near the cemetery where she is buried. I had not seen her grave since I was a child. I think her son, Jim, pointed it out to me. I wasn’t exactly sure where her headstone was, but I remembered the vicinity. As I started wandering, I found it, nearly right away.

I stood over the place where her bones are in the earth, and I thanked her. From her, I’ve received life. From her, I’ve received steadfastness. From her, I’ve received a resolve to keep working toward the repair of relationships and communities, even when the path is slow and uncertain. To be clear, this is not a call to endure harm or remain within relationships or systems that cause it. But it is a call to discern carefully where repair and wholeness are possible — internally, for sure, and if conditions allow it, in relationship — and to express gratitude when it is.

I do not always know how to do this. But I want it, at least in part, because of her.

—Renee Roederer