One year ago, after the inauguration, we began to experience an onslaught of executive orders and threats — making sweeping changes, canceling grants, and negating existing rules. It was remarkably overwhelming. Steve Bannon later said the strategy was deliberate, naming it “flooding the zone.”

One year later, it feels like the zone is being flooded again, but this time on the world stage. It’s not one major crisis or a single impending set of threats. It’s Venezuela. It’s Minnesota. It’s Iran. It’s Greenland. The sheer volume makes it hard to know where to look or how to respond.

In the midst of this, I want to share something Eli McCann recently offered. As a gifted humorist and storyteller, he’s a TikToker with a large following. He shared something his Mom used to tell him growing up.

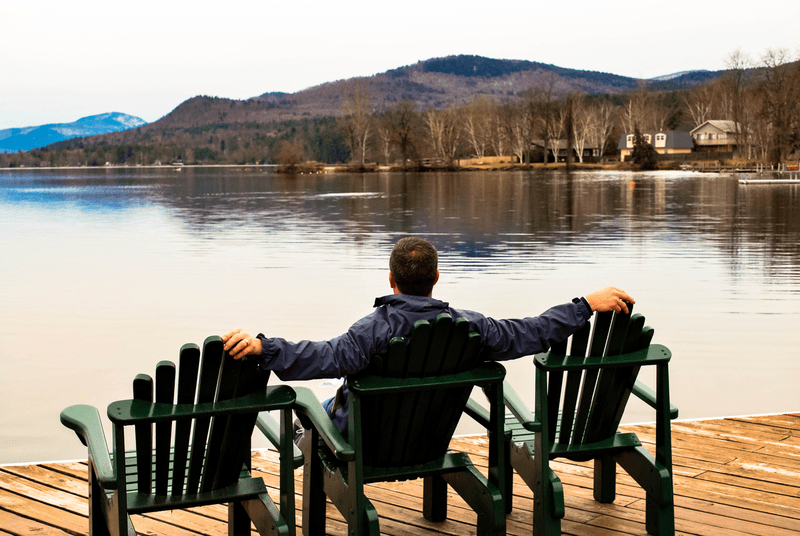

When so many waves of chaos, impending threats, and massive change hit at once, it is completely understandable to feel panicked or despairing. When those feelings show up, we can care for them within ourselves and alongside others. But ultimately, as Eli McCann shared, his Mom would tell him that staying in panic or despair isn’t productive.

Instead, she encouraged him to ask himself a question: What is something I can do today, in my own sphere of influence, that will make the world better? What is something I can actually do?

It’s a simple question. And I also think it’s remarkably helpful. It’s easy to look in all directions and either feel overwhelmed or believe we’re powerless. But we are not powerless.

What can each of us do, right now, in our own sphere of influence, to care well for what’s unfolding — and to help build collective change? Sometimes that question is where steadiness begins.

—Renee Roederer