As of today, we are more than halfway there.

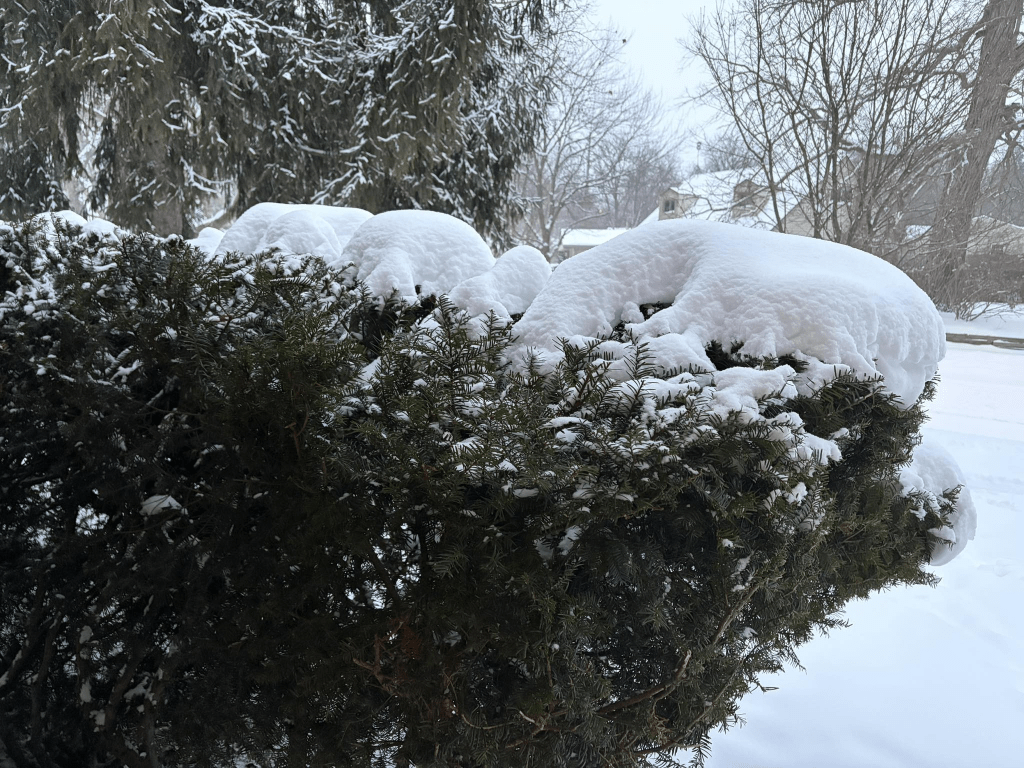

Over the weekend, I learned about Imbolc. I had never heard of this holiday before, but it is an Irish tradition of honoring the halfway point between the Winter Solstice and the Spring Equinox. Imbolc was yesterday, so as of today, we are closer to the first day of Spring than the first day of Winter.

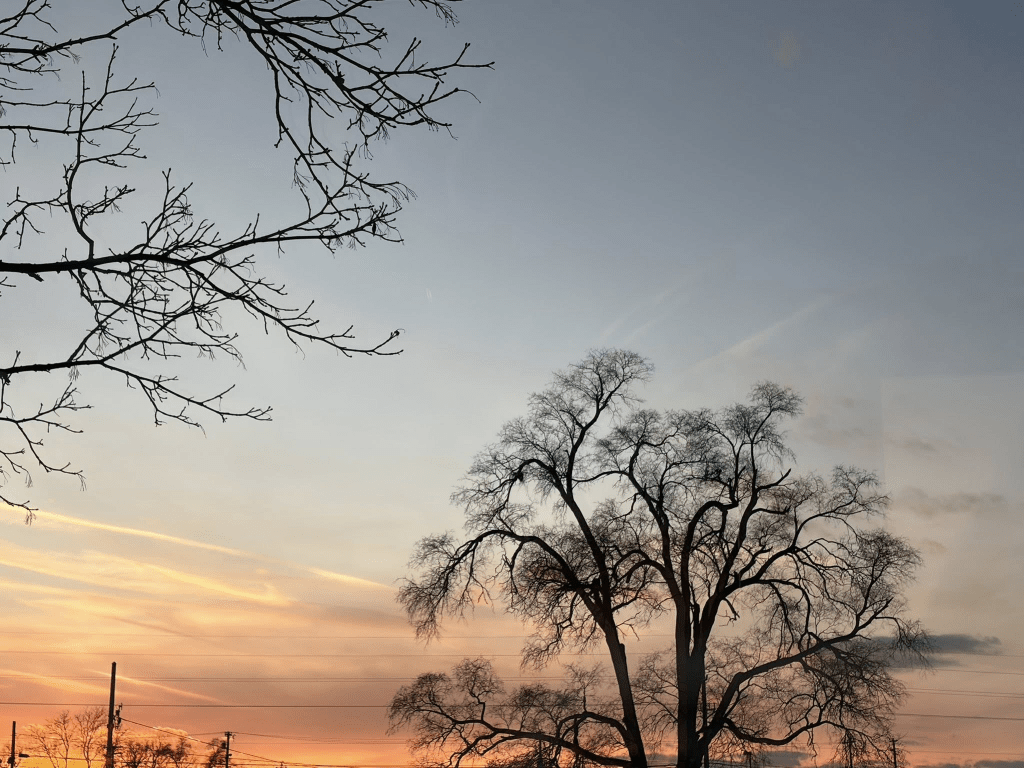

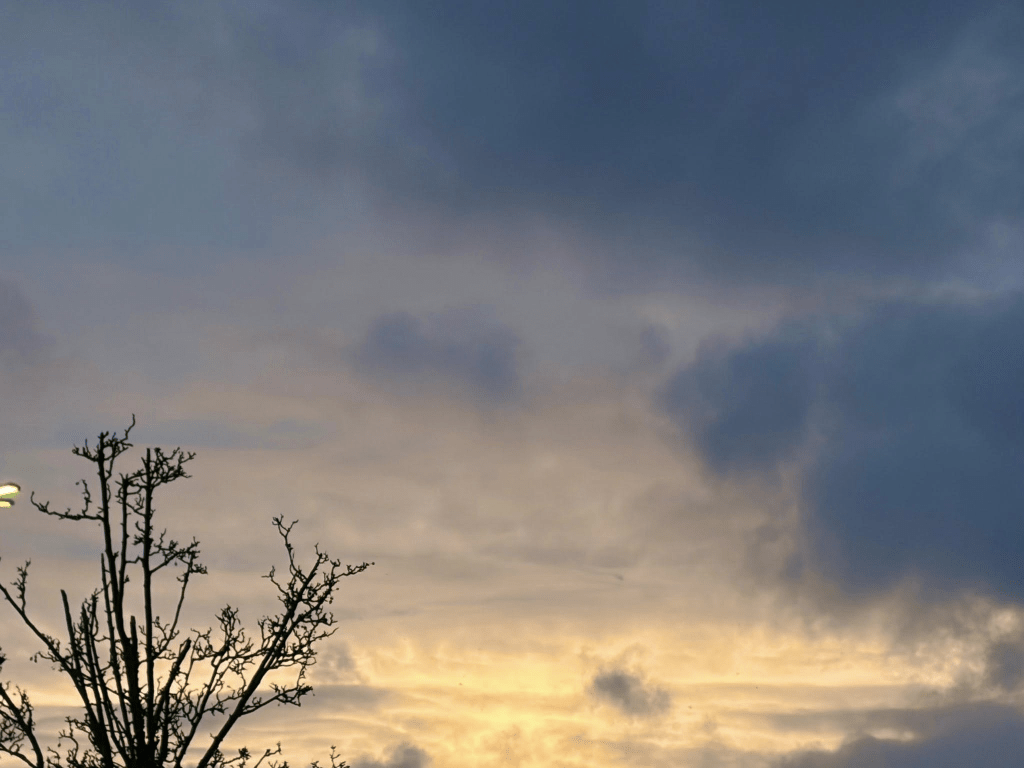

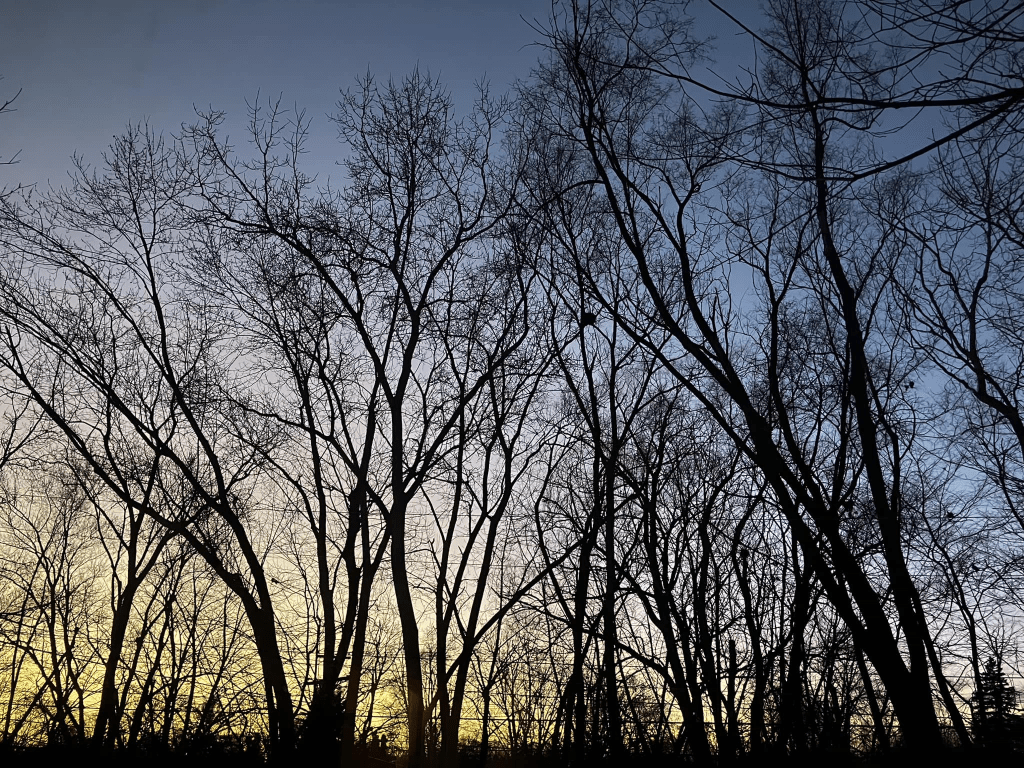

My dear friend Cole introduced me and our shared community to this holiday, and they offered an opportunity to observe and reflect as well. Cole invited us to take note of the sunset every day from now until Spring. We are fortunate that we have this time marked on our phones down the minute. They suggested that we take a few minutes to look out a window at sunset and also ask ourselves some good questions:

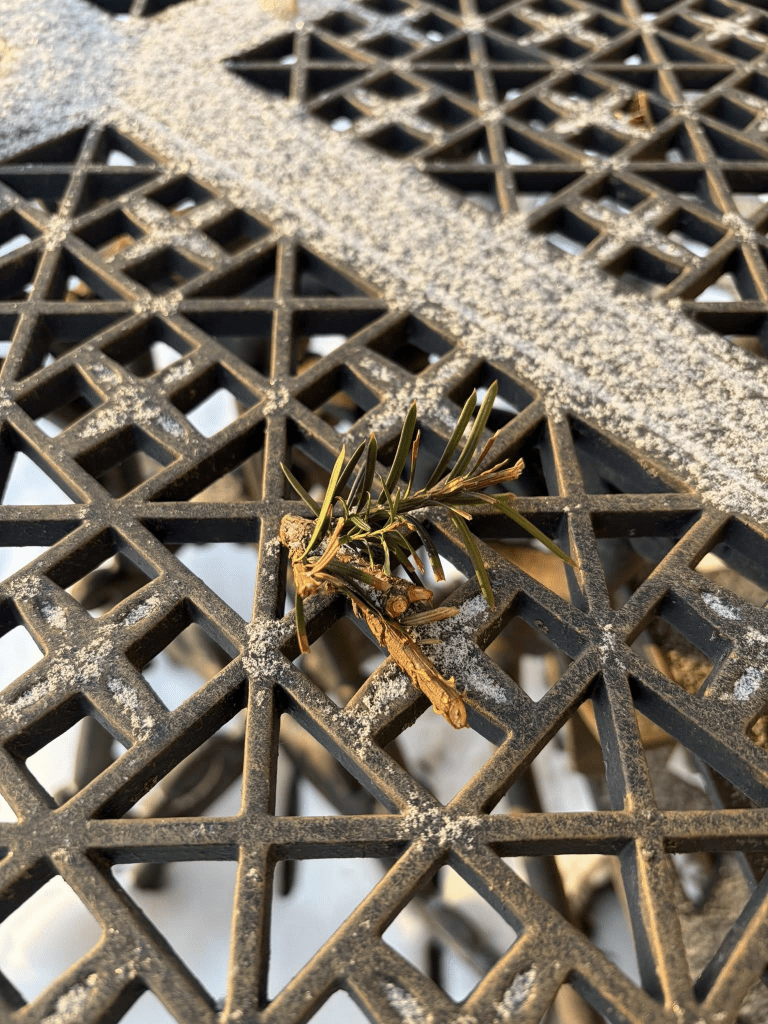

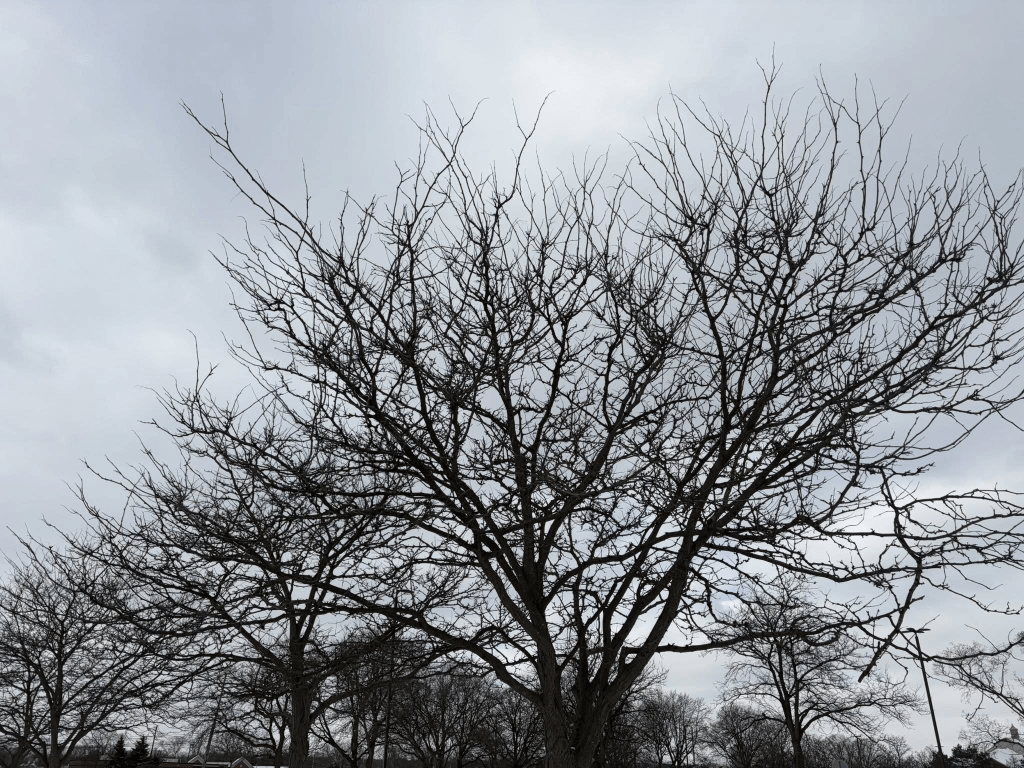

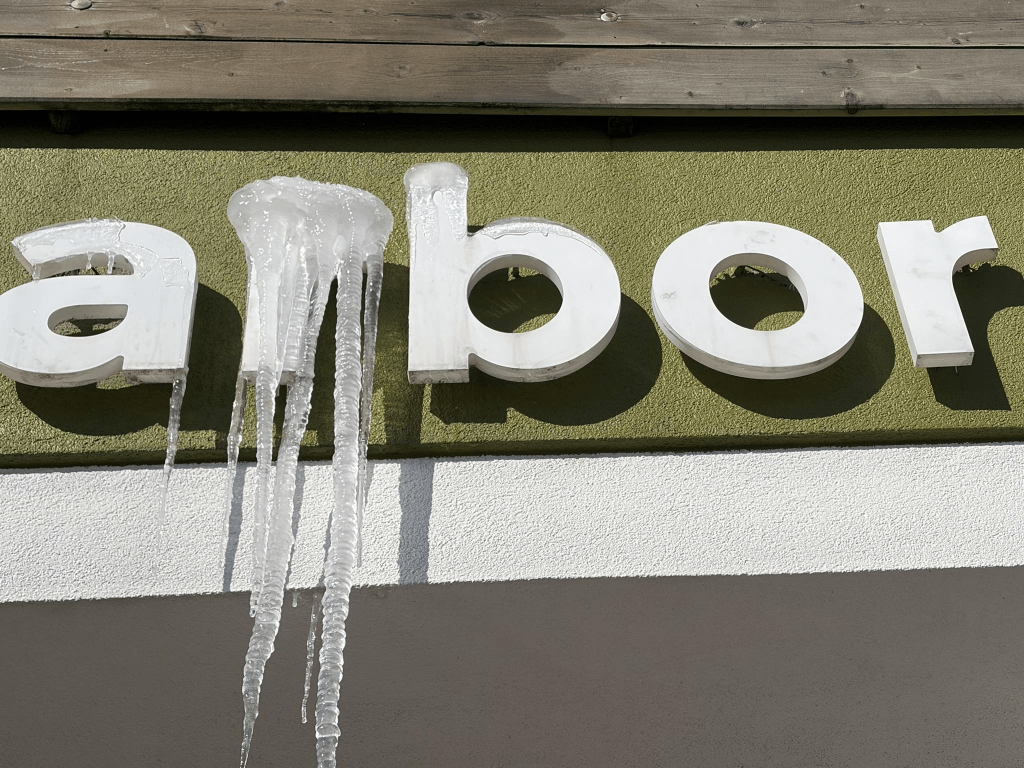

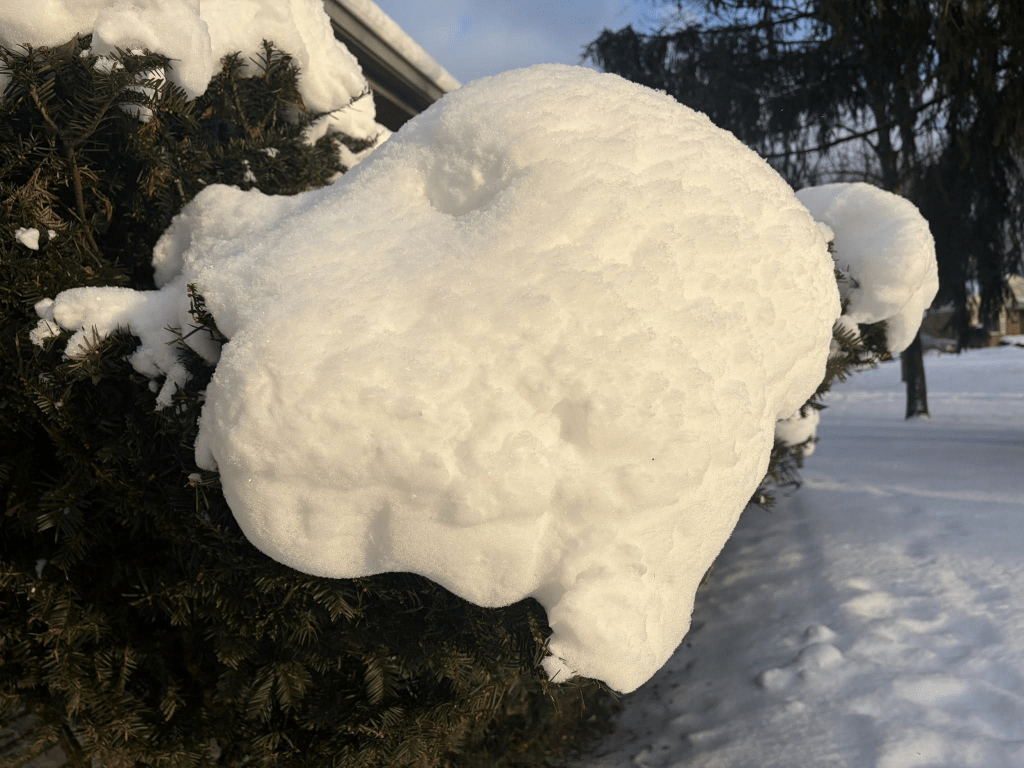

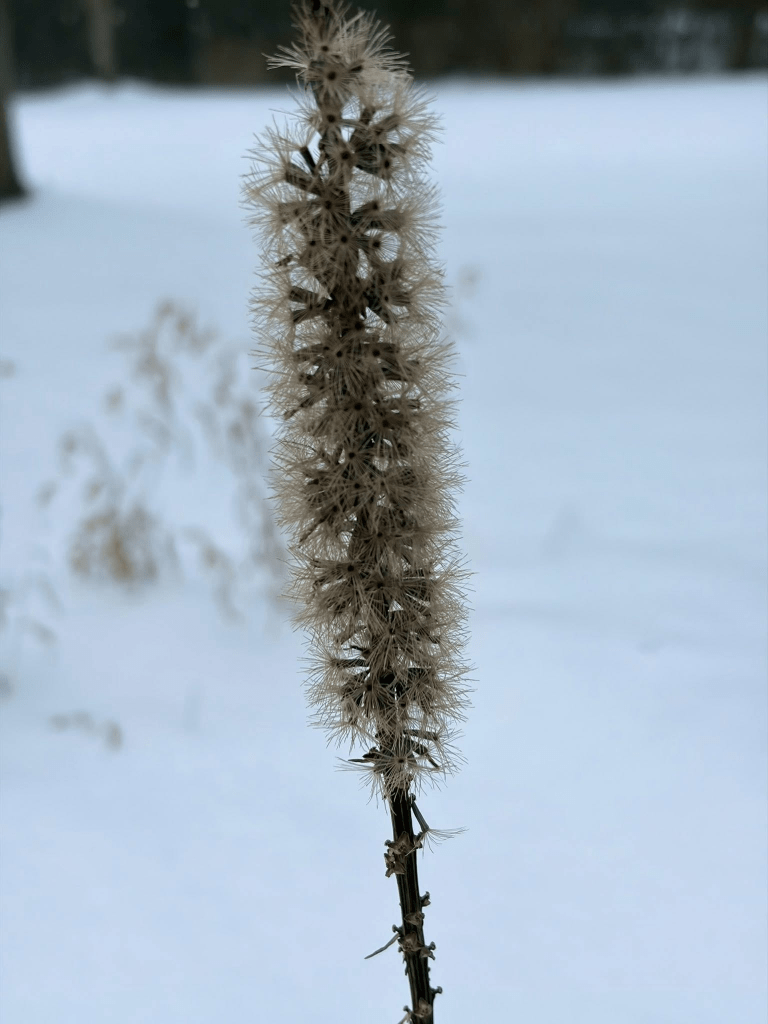

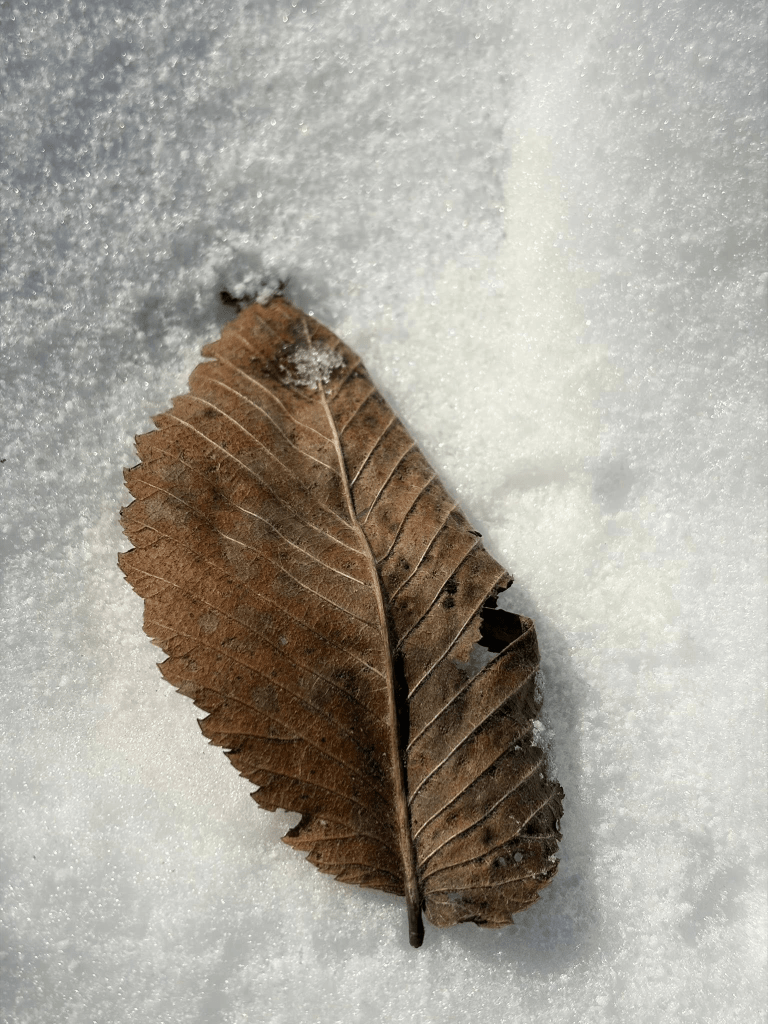

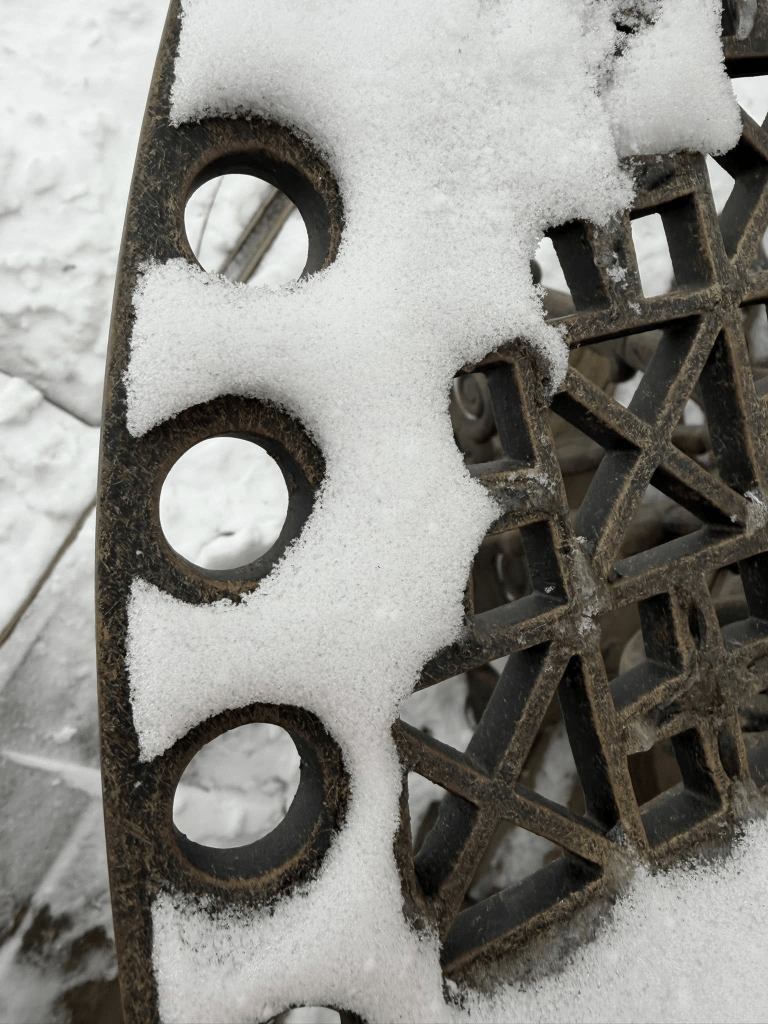

What is changing? What does it feel like to connect with the lengthening days? What do we see melting or eventually budding? What is changing inside of ourselves? What forms of newness are being born right now — inside us, inside community?

With all of this in mind, I close with another question:

Would you like to observe this with me?

—Renee Roederer