— Photos by Renee Roederer

Here’s a great podcast episode, released by Radiolab.

Description:

Until recently, scientists assumed humans were the only species in which females went through menopause, and lived a substantial part of their lives after they were no longer able to reproduce. And they had no idea why that happens, and why evolution wouldn’t push females to keep reproducing right up to the end of their lives. But after a close look at some whale poop, and a deep dive into chimp life, we find several new ways of thinking about menopause and the real purpose of this all too often overlooked second act of life.

This is an intriguing episode: The Menopause Mystery

Maybe we’re in them now. Or if some of them have changed, or even gone by, maybe we can reclaim parts of them. Maybe we can make them feel present again.

I’ve been thinking about a particularly vital social role — one that can shift the atmosphere of a room, change the dynamics of a community, and ripple through the broader culture we share.

We know how hard it can be to go against the grain and name a truth that’s uncomfortable, especially when social forces are at play that prefer to deny that truth or look away entirely. Naming these truths is a brave and necessary role. But it’s not the only one.

You probably don’t have to reach far to think of examples:

Naming a painful family dynamic.

Naming systemic racism.

Naming active harm and the need to protect marginalized people, especially when those very people have been politicized, diminished, or distorted in the public sphere.

It’s not difficult to see that these truths need to be spoken. But it is difficult to be the one who says them out loud. That moment carries risk — sometimes social ostracism, sometimes punitive consequences. And that’s why there’s another role that’s just as crucial: the role of the one who seconds the truth.

The one who says, “Yes. I see that too.”

The one who gives their weight to the boat being rocked.

The one who helps shift the equilibrium so that more people can rise and speak.

Years ago, a friend shared an image with me from family systems theory. Imagine a group of people in a small fishing boat. One person stands up, perhaps to draw attention to something important. But by standing, they throw off the balance of the boat. In that moment, everyone else has a choice. They can try to pull that person down in an effort to restore the old equilibrium, or they can shift their own weight — literally moving their bodies and changing their positions — to create a new equilibrium.

There is power in standing with the person who stood up. There is power in backing a community that says “no more.” There is power in seconding the cry of the harmed and the marginalized, and making space for others to speak too.

This week, I found myself thinking about Jesus’ story of the Good Samaritan. It begins when someone asks, “What is the greatest commandment?” Jesus answers: Love God with all your heart, soul, strength, and mind, and love your neighbor as yourself. Then the man follows up, “And who is my neighbor?”

Jesus tells a parable with a surprising twist. The hero is a Samaritan, a person who, in the eyes of Jesus’ audience, was socially maligned and religiously distrusted. Jesus doesn’t just tell us to be kind; he challenges the very systems of who gets to be considered good, worthy, and neighborly. He lifts up the one who had been vilified.

In telling this story, Jesus isn’t only standing up. I wonder if he may also be seconding something he saw recently — Samaritan who had acted in love, or perhaps someone who had recently defended a Samaritan and faced backlash for it. Maybe Jesus is making space for more people to say, “We’ve maligned Samaritans in harmful ways, and that has to change.”

Sometimes the first person to speak pays a cost. But those who follow — those who second and third the truth — can turn one voice into many. They can spark a domino effect that allows communities to change their posture, to shift their weight in the boat, and to make a new kind of balance possible.

We need those people.

We can be those people.

We can allow the boat to rock.

— Renee Roederer

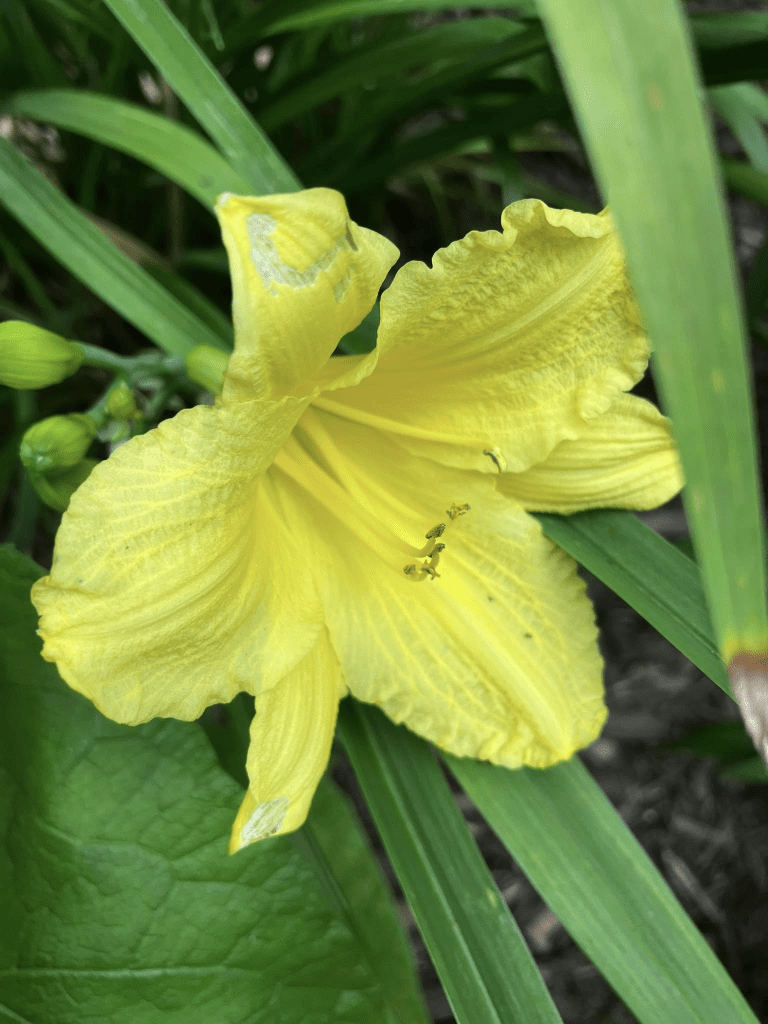

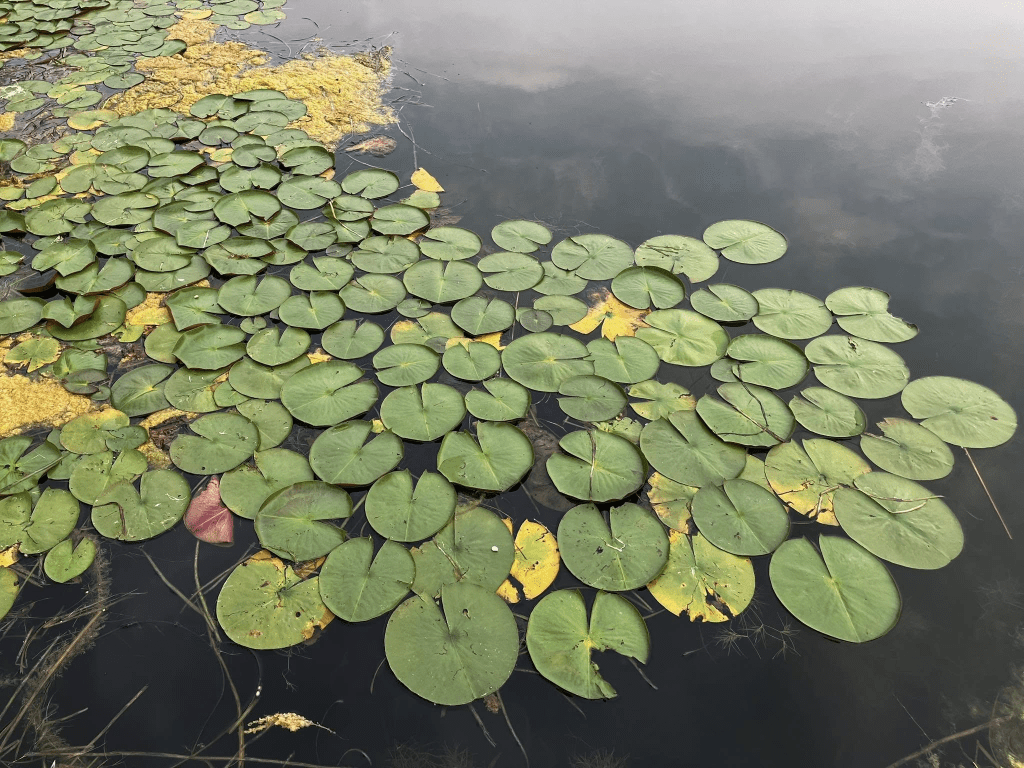

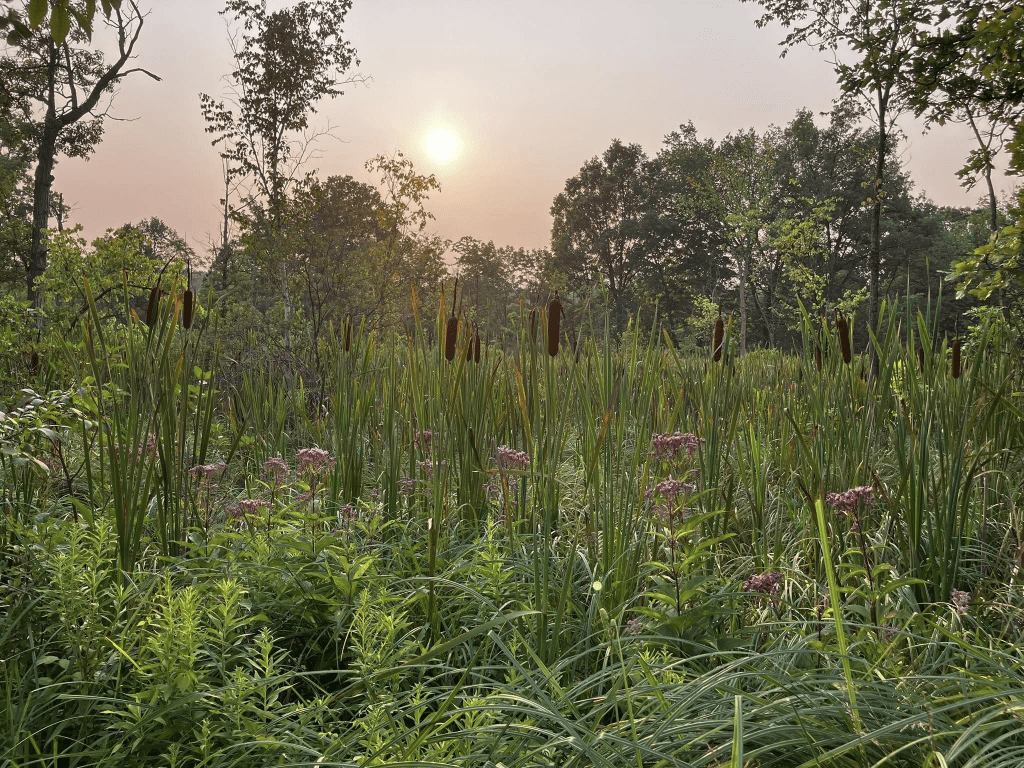

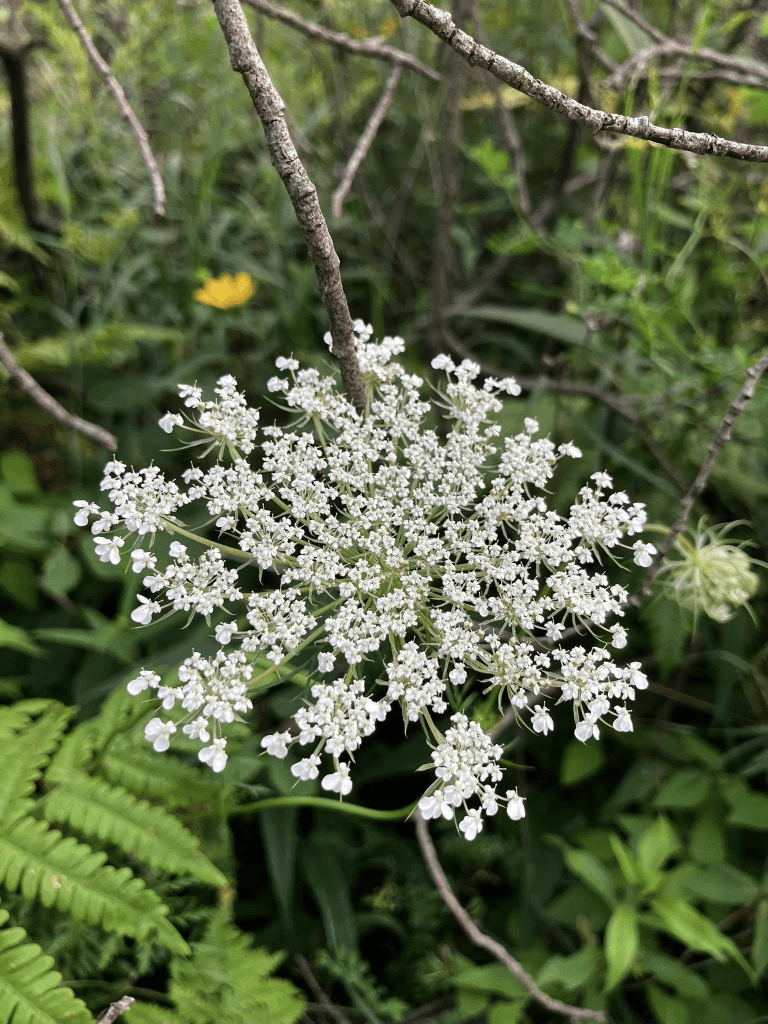

This week, I’ve taken some lovely walks at Metroparks in Southeast Michigan, and I’d love to share.

—Photos by Renee Roederer : Kensington Metropark, Huron Meadows Metropark

I was riding my bike down a street when I saw large, square banner at the end of someone’s driveway. It had a black background with white writing. Before I read its content, those are the details I noticed. All of those markers prepared me to read a religious message. Something like, “If you died tonight, do you know where you’d go?” or maybe a different message you might find on a proselytizing tract.

But that’s not what it said.

It said, “How do you know you won’t be next?”

As in,

When an authoritarian government is harming some in this particular country, within a world where authoritarian governments are harming some in additional places, perhaps this is not the time to simply shrug our shoulders and say, “Well, at least it’s not me.”

How do you know you won’t be next?

Maybe it’s hard to lean into that question. And if you’ve read me for long, you certainly know I’m not a doom and gloom writer. I believe in hope. I believe that grace often smuggles its way in. But I also believe there is truth to what Martin Niemöller wrote so poignantly:

First they came for the socialists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a socialist.

Then they came for the trade unionists, and I did not speak out—because I was not a trade unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out—because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me—and there was no one left to speak for me.

From my bike, I expected a banner rooted in a particular theology of hell. Instead, I received a banner that reminds me we are capable of creating hells on earth for one another. And sometimes, we are unwilling to prevent them.

I’m tempted to circle back to that hope, but instead, I’ll let the question linger because it’s a vital one:

How do you know you won’t be next?

— Renee Roederer

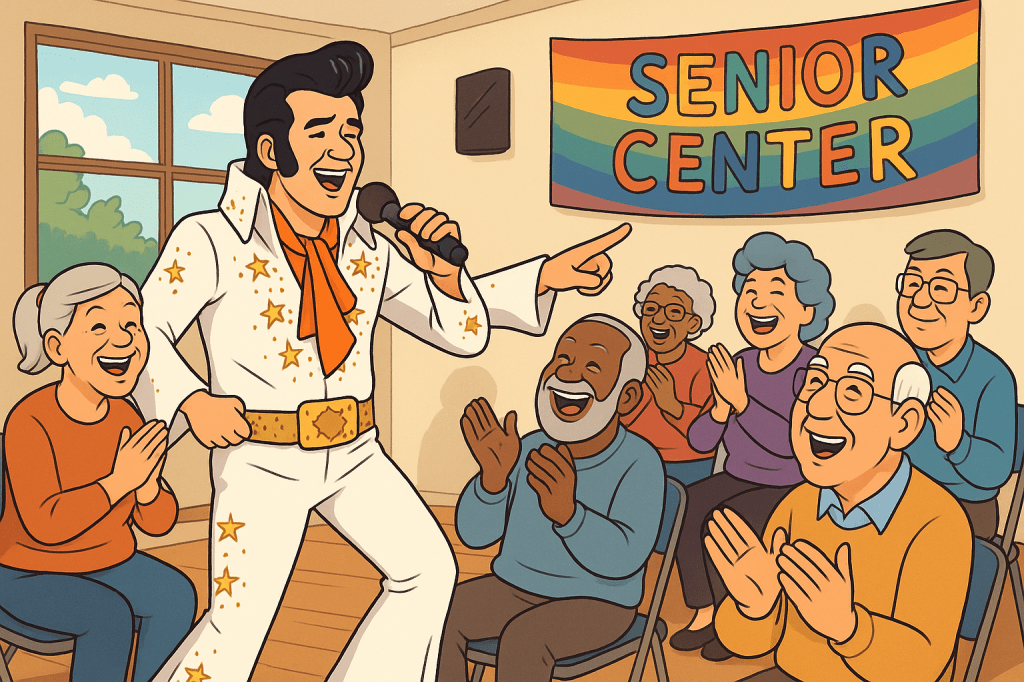

I received a text from a senior I know:

“An Elvis Impersonator came to my exercise class!” Sure enough, my phone had an image of my loved one with the King. (Or a King Wannabe). And this felt very on-brand. She would love this kind of thing. And that made me smile.

Once I had a chance to talk with her, I learned more. She’s been going to a Senior Center with a friend for an exercise class, and as part of this program, they get a free meal afterward. Upon learning more, I heard that seniors can take these meals home, too. “And sometimes, they’ll deliver them to you,” she added.

That’s when I put two and two together and understood that Meals on Wheels is partnering with the Senior Center in this way. I began thinking about how important this is: Seniors have an opportunity to get movement for their bodies, have social connection, sit down for a meal together, or take food home, or sign up some of their own loved ones to receive what they need at home, too.

This is all care. When it comes to health outcomes, it’s also prevention. What’s that phrase? An ounce of prevention is worth a pound of cure? This seems like such an incredible example of that. This keeps seniors connected. It benefits their finances. It makes them less likely to end up in the hospital. And if they do have serious health needs, they have both staff and a circle of peers to check in on them. And on top of all of that, they’re receiving Elvis to boot.

I also found myself sad, thinking about how these kinds of programs are experiencing funding cuts. I wonder how many of those seniors are aware that these very kinds of programs are in danger of drying up. I hope that won’t be the case for this particular set of offerings I’ve described. But I know it’s going to happen somewhere, or even a lot of somewheres.

I continue to be moved by people who have the vision to create such compounding benefits for their communities. We’ll also have to do the work to ensure they receive the funding they need.

— Renee Roederer

When I clicked on a link to this video, I thought, “This is probably too long to share.” But upon pushing play, I found myself very intrigued, and I think this is worth it. Enjoy!

Hubs are essential — people and communities working in connection rather than isolation. When we move away from silos and toward collaboration, everyone benefits.

This week, I found myself using the word “hubbing” as a verb. It’s not a common word, but maybe it could be. Hubbing is something we can do intentionally. In any setting of care or support, we’re better served when different pieces are connected to the whole.

More than a decade ago, I served as a pastor in a congregation that joined a consortium of congregations. Together, we coordinated care for the broader community. One congregation ran the food pantry. Another provided bus tickets. Another offered help with utility bills. Another hosted a clothes closet. When someone came to any one of us with a need, we didn’t just respond individually. We could connected them to all of these services collectively.

Today, at the Epilepsy Foundation of Michigan, we’re doing something similar. We’re working alongside other organizations through a grant that helps build and connect transition services for youth and young adults with epilepsy. This includes moving from pediatric to adult healthcare, from middle school to high school, into college or vocational training, into the workforce, and toward supportive, independent living. The leadership team spans multiple organizations, and we’re reaching out to even more.

Hubbing is vital. It helps streamline care, coordinate efforts, and most importantly, get people to what they need — not in fragments, but toward the whole.

— Renee Roederer