The Beauty of Change

A couple of days ago, I was driving around my town. With a smile on my face, some words just spontaneously tumbled out of me. “I know you,” I said, and then I smiled some more.

I spoke this to Ann Arbor, the place I’ve called home for the last twelve and a half years. My car windows were down, and I took an enormous, intentional breath of spring air. Then I put my arm out of the window to feel the breeze. I felt very alive.

The reality of spring called those words forth from me.

“I know you.”

I continued to enjoy the spring air, but the visual scene was most responsible for bringing those words into being. In Michigan, we have entered an aesthetically gorgeous time of year. The six month period from April to October brings continual changes in scenery.

Each week shifts as a variety of flowering trees and plants emerge, soon accompanied by the newborn leaves of trees which grow in gradual ways. After these leaves progressively paint our town bright green, they rustle in the wind for a few months and finally give us a swansong, bursting into a variety of colors as they shed their photosynthesis process and reveal the red, orange, and yellow colors hiding underneath it.

For this half of the year, every week is gorgeous, and every week is gorgeous differently.

This is the twelfth spring I’ve experienced in Ann Arbor, and I’ve lived here long enough to know the order of this unfolding process of change. That’s why the words tumbled out of my mouth that day in my car.

“I know you.”

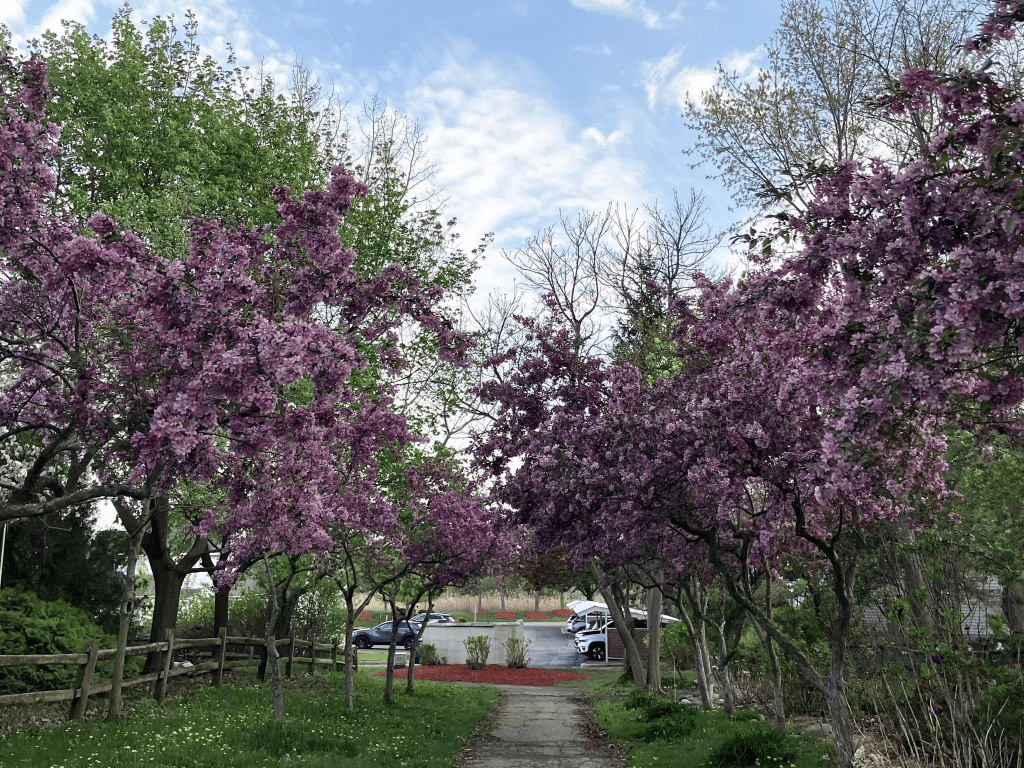

I know how one set of flowers and blooming trees emerge and seem to reign for mini-era of time, only to be replaced by another set of flowers and blooming trees. It’s a beautiful procession.

I know that the daffodils,

soon give way to the bradford pears,

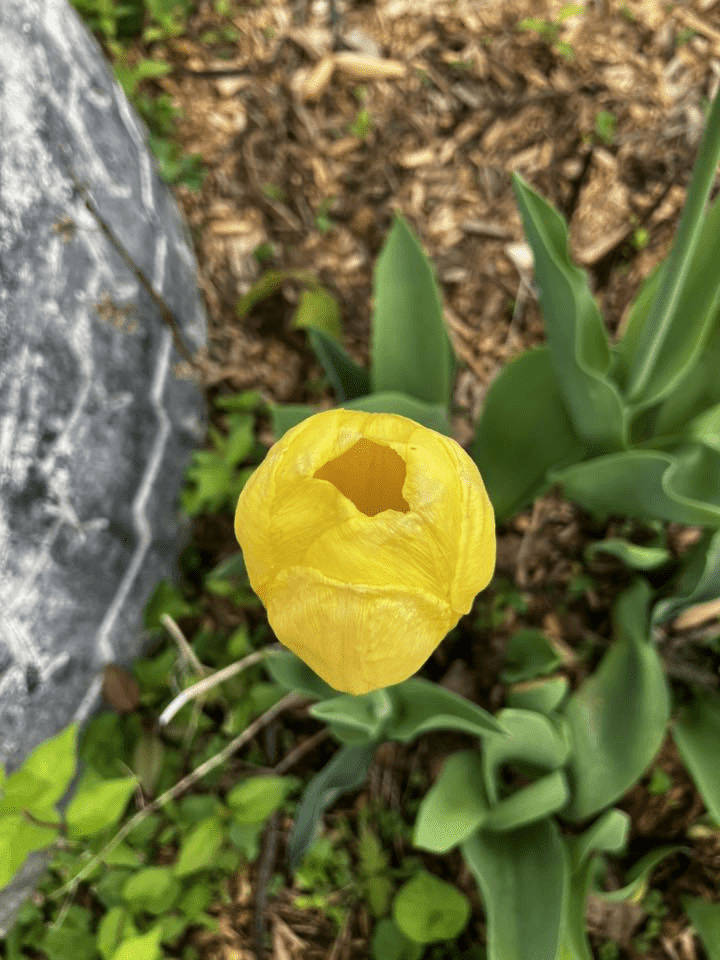

which soon give way to the tulips,

which soon give way to the tulip magnolias,

which soon give way to the day lilies.

This process continues to unfold beautifully.

I love that we are in the midst of this procession right now, and it gave me an impromptu burst of joy when I spontaneously said, “I know you,” to Ann Arbor on that day.

There is a rich experience of belonging when we feel at home.

This is true

within places,

within relationships,

within ourselves.

We can feel at home in the presence of all of these.

When we do, I think we have some knowledge of the essence of what is before us, while also knowing and even expecting that it will experience change.

For instance,

I know the order of Ann Arbor’s flower procession,

but I am still surprised by its emerging beauty.

Likewise,

We know some of the essence of our children’s personalities,

but we are surprised with their growth year by year (and even daily).

We know our weekly work routine,

but we are surprised when we feel a sense of calling within it or beyond it.

We know our personal traumas and forms of grief,

but we are surprised when new life and forms of resurrection find us.

“I know you.”

May we feel at home.

And may our experiences there change us too.

This Podcast Episode Will Do You So Much Good

I don’t even want to tell you what this is about. I invite you to listen to this podcast episode and be surprised by the dearest, most wholesome connections with people, including some intriguing science to boot. This will uplift you. I promise.

An Invitation to Play (Even Just a Little)

Are you carrying stress today?

Perhaps,

you didn’t sleep well, or

you have a looming deadline, or

you’re juggling a heavy load of responsibilities, or

you’re troubled by the news, or

you’re at wits end with your teenager, or

you’re in a conflict with someone you love,

or multiple expressions of these,

or something else altogether.

Whatever it may be,

you are worth

wellness,

space,

grace,

peace,

insight, and

connection.

And a moment of play serves as a reminder. Play reorients and grounds us in what is most true: We are loved and living in a world with lovely gifts, even as it contains real challenges.

Play changes our brains. It calms us and helps us feel more connected. It also shifts us away from our anxious reactivity, allowing us to use the higher levels of our brain functioning to solve problems.

So find a way to play a bit today, even if it’s just for a moment.

Today, I take my cue from a hilarious, adorable toddler. She has a really hard time continuing to sulk in that tantrum once she starts to delight in squeaky, red shoes. Enjoy this video:

And remember, you’re worth it.

Perspective (Give Yourself and Others Grace)

This is a tough time to be in transition—any kind of transition. Whether you’re coming of age and looking for your first job, considering new educational opportunities, moving, dealing with needs of aging parents, contemplating a career change, watching your kids leave the house, making a big purchase, or navigating something else altogether, it’s simply a challenging time. It’s not insurmountable, but it’s difficult.

Why?

So much is changing in our nation, and much of it feels uncertain. That doesn’t mean everything is dire, though some things may certainly feel that way. Some of it is just in flux. From “I’m not sure what’s going to happen exactly” to “I’m seriously worried about _____,” everyone in transition is carrying more stress than usual.

I overheard someone say, “In the midst of this, I feel like I always sound so woe-is-me!” And I thought, “No… it’s woe is us.” This is a difficult time.

But we are also the people who can help one another. There is a we that is stronger and more present than woe. So if you’re in transition and aren’t sure where to place your weight, let your relationships uphold you.

— Renee Roederer

Arbitrary Reality, Very Real Harm

I was in a car near El Paso, Texas, when I saw another city nearby. At first, I wasn’t sure what it was, but then I realized it was Juárez, Mexico. The city buildings were grouped in two areas, but the landscape between them was exactly the same. It made me think about how arbitrary borders are. One area flowed naturally into the other, but the conditions on the ground in each city were vastly different.

I also spent some time at Big Bend National Park, where the Rio Grande flows, marking the border between Mexico and the United States. There was no visible difference in the terrain. The view I saw was one continuous landscape; there was no divide to mark one side as fundamentally different from the other.

We often think about nationality as a fixed category, as though borders are a natural part of our lives. But in reality, they’re entirely man-made—arbitrary lines drawn by people.

Of course, these borders function in very real ways with real consequences. We’ve decided that some people belong based on where they were born, while others are excluded. Some have determined that human rights and constitutional rights apply only to those born on one side of an arbitrary line, not to those born just across the border, even if it’s relatively nearby.

A friend’s cousin is currently facing a deportation order. He was brought to the U.S. when he was just six months old, and this is the only country he has ever known. He’s a Dreamer and has worked previously as an organizer to create pathways to residency and citizenship for people brought to the U.S. as children. All his family members are citizens or legal residents. But just a week ago, he was with his girlfriend and two children when ICE surrounded him and detained him. My friend and their family are raising funds for his legal fees. Would you consider contributing?

Why is it seen as more egregious for someone to exist on one side of an arbitrary line we’ve created, yet not egregious to deprive children of their father? Why is it considered a moral violation to live in a particular geographical location, yet not to banish someone forever from the only home they’ve ever known? Where does the moral harm lie?

— Renee Roederer

This Week in Nature

Rah, Rah, Pom Pom Crabs!

This Memory Makes Me Chuckle

Last summer, I had the pleasure of visiting Pictured Rocks National Lakeshore with one of my very favorite people. This stunning national park is located in the Upper Peninsula, near Munising, Michigan. There are many ways to experience the beauty of these rock formations, but the best views come by boat from Lake Superior.

We were on a sunset cruise, and it was gorgeous. After boarding the boat, we heard an announcement over the loudspeaker:

“Hello, my name is Braden, and I’ll be your captain on our sunset cruise tonight.”

My friend leaned over and whispered,

“We’re old enough… to be captained… by a person named Braden.“

The Bradens are coming of age, and it’s a reminder of our own age.

This memory always makes me chuckle.

— Renee Roederer

Keep the Main Characters the Main Characters

I recently heard a perspective from a Dad of a Trans son that resonated with me. He said that too often, we make Donald Trump the main character of all that is unfolding.

This wasn’t an argument to minimize what’s happening—not at all. But it does highlight the ways we frame what is taking place. We all know how much the news focuses on Donald Trump, and I can’t help but see it constantly in my own life. Even when I’m at work, I glance at the bottom of my laptop screen, and there it is—“The Trump Administration” as a teaser, trying to get me to hover over those words and receive some “Breaking News.” But this Dad, who loves his son deeply and wants to keep Trans youth alive, as should we all, pointed out that it’s an extra wound to make Trump the main character of the harm he’s causing his son. His son should be the main character in his own story, and so should so many others who are deeply impacted by these words and policies.

The harm caused by Trump’s rhetoric, especially to marginalized communities, is undeniable. But by consistently centering him as the protagonist in this story, we diminish the actual people who are suffering. His son, in this case, deserves to be the main character in his own narrative, thriving and living fully.

This is also true when it comes to immigration, detention, and deportation. We need to center the stories of people like Kilmar Abrego Garcia, Mahmoud Khalil, and countless others whose lives have been upended by policies that target them. Just last week, a mother was deported to Honduras with her children, who are U.S. citizens. One of those children, facing stage 4 cancer, was sent away without needed medication. This is cruel and heartbreaking. These are the people who deserve to be the main characters in this story. Their stories—their struggles, their humanity—should be our focus as we tell these stories.

And let’s not forget about past moments, too. People were rightly outraged when then-candidate Trump made fun of a disabled reporter on the campaign trail. But how often did you hear that disabled reporter’s name—if ever? His name is Serge F. Kovaleski.

The media should be lifting up the voices of those who are being harmed as well as those who are working to uphold individuals and communities during times of crisis. These are the main characters of this moment in history. We certainly don’t look away. This isn’t about minimizing harm. But who are we centering? Let’s make space for the people who truly deserve to be the focus. Keep the main characters the main characters.

— Renee Roederer