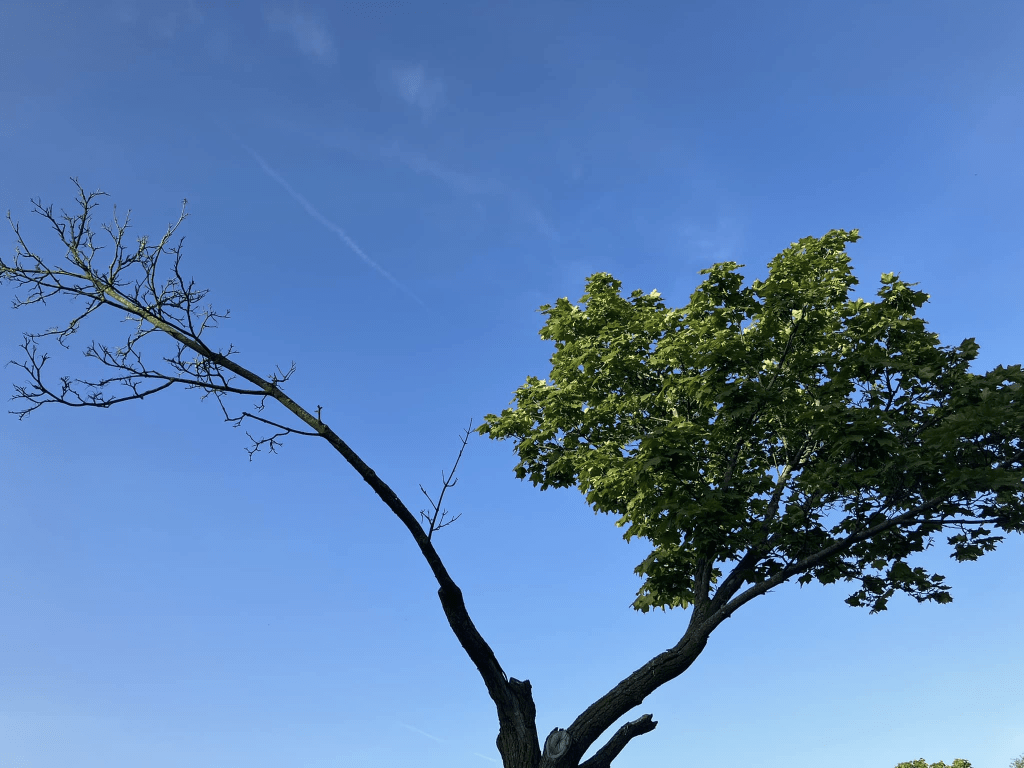

While taking a walk, this tree grabbed my attention. It’s a Parable Tree, and it can symbolize any message we each need to ponder.

–Renee Roederer

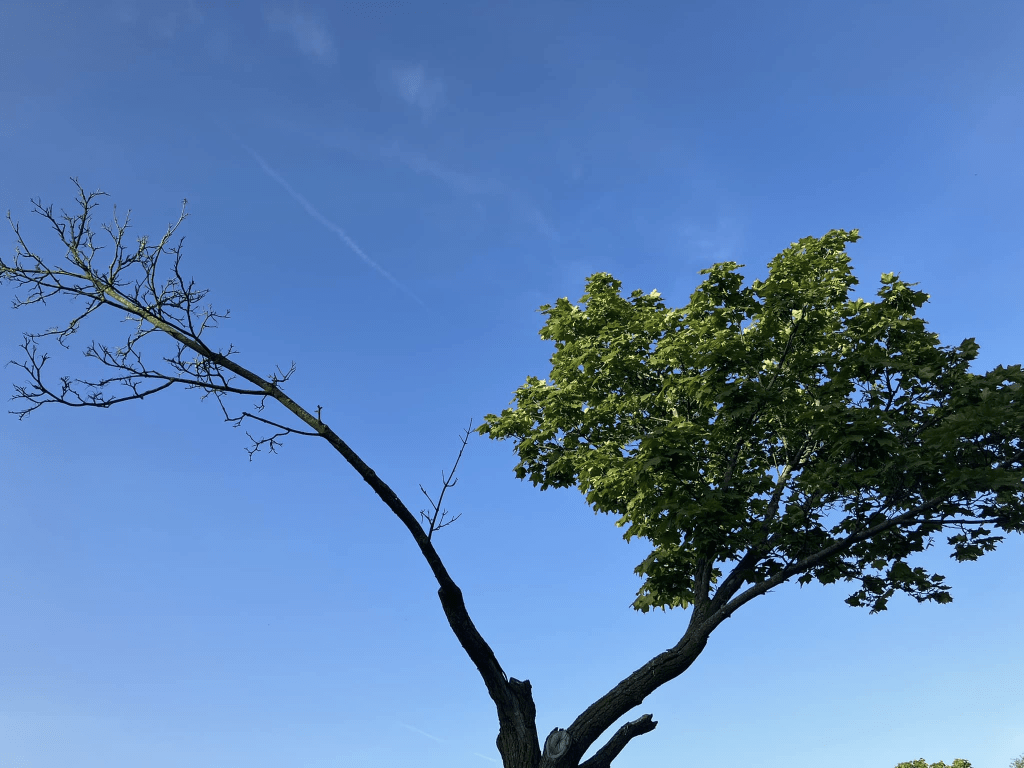

While taking a walk, this tree grabbed my attention. It’s a Parable Tree, and it can symbolize any message we each need to ponder.

–Renee Roederer

I walked among the congregation and called upon anyone who raised their hand. They were sharing joys and concerns with one another before we had a time of prayer. Folks shared about their neighbors and friends who were recovering from medical needs. Then a kind man raised his hand, and I walked over to him next.

“I’m glad you’re here!” he said.

I smiled and thanked him. I thanked all of them. “You always welcome me so warmly,” I added. I am a guest preacher for their congregation from time to time.

And that had me thinking back to something a colleague of mine once said. Rev. Denise Anderson said this (I’m paraphrasing from what I remember):

“There’s a big difference between saying, ‘You can come,’ and ‘You’re invited.'”

One is much more welcoming. In this community, I always feel the second. And I’m glad for any occasion when we can give from this message and receive from this message.

–Renee Roederer

Image Text:

When you debate a person about something that affects them more than it affects you, remember that it will take a much greater emotional toll on them than on you. For you it may feel like an academic exercise. For them, it feels like revealing their pain only to have you dismiss their experience and sometimes their humanity. — Sarah Maddux

My social media memories showed me a post I had shared on my Instagram story 4 years ago. Someone asked me, “What do you want?”

I read my list from four years ago, and I thought, “Four years later, I still choose these things.”

What do you want?

— A Big Chosen Family

— Laughter

— Storysharing

— Care Work

— Love/Access/Affirmation/Belonging/Self Determination for All Bodies

— Horizontal Churches (non hierarchical)

— Providing Resources for Each Other

— Belonging-Structures and economic systems build upon the intrinsic worth of people rather than their capacity for productivity

How about you? What do you want?

When we make space to be present to the moment before us,

When we create intention to notice the surroundings around us,

We are soon reminded of people.

Isn’t that true?

We walk around the grocery store and see a food item that someone especially likes.

We cross an email off our to-do list and remember someone we’d like to check in with later.

We smell a comforting scent and remember the people present in a long-ago memory.

The remembrances of people are around us all the time. This means we are invited into community all the time.

I find myself thinking about the word ‘remember.’ Though we don’t typically think about it this way, in English, the word is literally phrased as ‘member again.’ This is a way to express belonging. In community, we are members of one another. We belong.

There are times when we find ourselves mulling over the very same themes in our thinking.

There are times when we feel weighed down by longstanding frustrations that rarely seem to shift.

There are times when it feels like things are stagnant or unmoving.

So. . . What if we ask a different question?

This is something that a friend of mine says often, and I really appreciate it.

What if we do that? Could that open up new possibilities – creative pathways or new angles of relating?

Maybe that seems like a small thing, but it’s actually a large thing. Frameworks affect how we view situations, feel, and express hope.

So what if we try it? Might it open up something different?

What’s possible?

Over the weekend, I attended a Fundraising Gala for the Interfaith Round Table of Washtenaw County. La’Ron Williams, a community leader and professional storyteller, was one of the featured speakers. I was moved by what he had to share at that event. Afterward, I discovered he has an excellent TedTalk. I thought I’d share that today.

If we change the stories we’re telling —

stories we tell ourselves,

stories we tell about neighbors,

stories we tell about the world and reality itself —

we can change the nature of our relationships, and

we can change the world.

Every body is a good body.

Every body is a worthy-of-love body.

Every body is a worthy-of-care body.

Every body is a worthy-of-resources body.

Every body is a worthy-of-taking-up-space body.

Every body is a worthy-of-dignity body.

Every body is a worthy-of-connection body.

Every body is a worthy-of-self-expression body.

Every body is a worthy-of-advocacy body.

Every body is a worthy-of-self-determination body.

Every body is a worthy-of-having-needs body.

Every body is a worthy-of-tenderness body.

Every body is a good body.