new growth,

new emergence,

new possibilities,

can form

again

even in unlikely places.

new growth,

new emergence,

new possibilities,

can form

again

even in unlikely places.

These are baby purple basil plants. I was sad when I saw them wilting inside their planter container. It will be time to plant them in a proper pot soon — that, I knew — but goodness, their stems were all totally wilted, lying flat over their small mounds of dirt.

So I put these small mounds of dirt into little clear bowls. Then I put some water in the bowls. These little babies sucked that water right up, and in very short order were springing right into growth again. It was amazing to witness how resilient they were.

And that had me reflecting…

Sometimes, you have to change the environment. When that environment has good, solid resources and care… much is possible. Sometimes, much more than we think.

Isn’t that also true when it comes to ourselves? Our neighbors? Our relationships? Our communities? Our world?

In what seems like two days ago, I stood in the backyard and thought, “It will be time for the hosta plants soon.” They weren’t there yet.

It really does seem like that happened two days ago! But then again, ever since the pandemic began, I have no fully accurate sense of time. Post-pandemic time is Jeremy Bearimy. Maybe it was last weekend. But it certainly wasn’t a long time ago.

Then, yesterday evening, I looked out side, and what? There they are. They had sprung up, all together, and quickly.

It’s a reminder that sometimes… growth happens quickly. Yes, most of the time, it happens slowly with lots of twists and turns, but sometimes — maybe out of necessity? — it comes quickly. We can welcome it when it does.

If you close your eyes and awaken your awareness,

If you inhale deeply and let that breath fill every part of your being,

If you allow yourself to sit with the Question —

really and truly, as if you were taking it out for tea,

it will inhabit you,

it will enliven you,

it will call you by name,

and you will know what I’m talking about.

You will be familiar with the Question,

because it keeps making itself familiar to you.

It is that Question that keeps rising again

inside your being,

like an enormous, beckoning moon,

and the mysterious tide She consistently summons.

Yes, listen.

Stand on the shore of the horizon

and welcome the Question revealed in the waves

of

longing

lingering

dreaming.

. . . that Idea that keeps returning,

. . . that Love that keeps emerging,

. . . that Path that keeps arriving,

Listen. . .

In the swell of waves,

Ah, there it is –

Won’t you?

It sounds for you –

Won’t you?

Hear it resound and expand –

Won’t you choose that which is choosing you?

In times of high stress and collective trauma (oh, you know, what we’ve been living for at least 7 years straight… compassion for us) sometimes older narratives of stress and trauma get pulled to the surface too. We might be aware that these are getting triggered. Or we might be less aware.

It’s helpful to bring these to awareness. As therapist Margaret Foley says, “If we have unprocessed material deep inside, we have two choices. We talk it out, or we act it out. We reenact what we have not resolved.”

These unresolved reenactments can become large narratives in our present-moment lives, but they are out of place and out of time. Or they might weave within our present-moment situations. Have you ever felt that your reaction to a present challenge is a bit oversized and disproportionate to the moment? Older stories and older emotions might be getting triggered too.

Within all of this, sometimes we look for people — close loved ones (frequent) or people of less personal significance (less risky) to play roles in our reenactments. We cast them as characters in the drama, and they serve as placeholders to hold these stories. They become containers to store our old emotions. But this can really harm relationships too.

Common containers include:

The role of the rescuer. We cast people as characters to save us. We want to be seen in our vulnerability (valid) but become dependent upon others for our feelings of safety. We externalize that need because we struggle to feel safe internally.

The role of the villain. We cast people in the character of scapegoat, attempting to funnel our pain into them and send them off. This is really an attempt to rid ourselves of our own anger and pain.

The role of the stand-in. We cast people into the character of a significant person in our lives. We begin to engage this person with the emotions we actually have for our mother, or father, or sister, or brother, or estranged friend, or person we miss, or person who wounded us.

I speak about all of this as a care-worker. I see this happening so frequently in this era of time. This comes from a natural place of wanting to heal pain, and it makes sense for this to happen after years of collective trauma. Of course, this would unearth old narratives. I also speak about this as person who lives in this era of time, witnessing and feeling my way through all of these things too. The challenge is, people aren’t asking to find themselves in the cast list of our internal storylines — unless, they themselves, are reenacting their own traumas by stepping into these roles too (that happens also!)

We can add care to others, but we aren’t rescuers.

We can make mistakes, but we aren’t villains.

We can care about the emotions people have for significant individuals in their lives, but we can’t become the stand-ins for those particular people.

Role-casting might bring some initial relief, but it also doesn’t work. We have to actually process the unprocessed material and storylines.

That’s the harder, but more life-giving work. Sending care to all of that.

One of my youngest family members went viral this week. With more than 1.5 Million views to date, she’s a sweet superstar.

Enjoy this sweetie who just needs say Hi to a Grocery Store Cowboy:

To my shock and annoyance, there are ants in my bathroom this morning. Thankfully, the place isn’t inundated, but the searchers are searching in a noticeable way. I was so surprised when I went in there this morning and saw them. After all, there is no sugary goodness for them to find to tell their friends about. By not-inundated, I mean, I don’t have oodles of them walking in a defined line (thankfully!) but when I came in there, they were moving in various directions, searching.

I decided I wanted to encourage them to run away, so I turned the water on, and sure enough, they moved faster. Then I took a hairbrush and hit the counter with it repeatedly to make some sound, though I’m sure it’s the vibration that does it. They began skidaddling even faster.

And what did they do? They ran toward each other, following the left-behind-scent so they could meet up, communicate, try to steer clear of my bathroom (c’mon guys, search better) and move away from stress together.

I thought, hmm… that’s not often what humans do.

In times of stress, we sometimes withdraw, hunker down, isolate, and tell no one.

Yesterday, on an ant-free-day, I stopped off at my local coffee shop before driving to work. I was walking in, motivated and ready to go for my day, and… SPLAT. I fell hard.

There was a water pipe in the asphalt, and some of the asphalt that typically surrounds it had broken off. My foot caught that, and I fell so quick. I didn’t have time to brace myself. I fell hard on my knee, in particular, and thankfully my hands caught me instead of my face. And it hurt so bad. I felt confident that I had not broken anything or hurt anything irreparably, but it was big pain. Knowing now that I was and am okay, it’s okay laugh at this next part. I mean, I did:

When I fell, my shoe came off behind me, and the cup previously in my hand was thrown out a ways before me. It reminded me of moments when a person is skiing, falls, and loses their skiis and poles. That’s called a yard sale.

Basically, I did an asphalt parking lot yard sale.

In my newly flattened state in pain, I cried out. And there was a person sitting outside enjoying coffee. He said, “Honey, you alright?”

Flat girl me: “Yes” (gets up slowly and majorly winces) “but thank you so much.”

Nice, coffee drinking person: “Do I need to come get you?”

Standing up, ouchy me: “No, but I greatly appreciate your offer. Thank you. I think this is the kind of fall where I need to walk it off.”

So I walked toward my new coffee friend, and we smiled that I could do it. Later in the day, I would discover that my knee was still hurting — again, not broken or torn — and that there will be a heck of a bruise.

But we came toward each other in that moment. And that’s what we needed to do. Thanks, nice coffee drinking person.

No hairbrush needed.

—Renee Roederer

I greatly appreciate the book Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds by adrienne maree brown. The book opens up analogies to us through biomicry, inviting us to learn from nature-inspired innovation and organize our human living, loving, and changing through these patterns of nature.

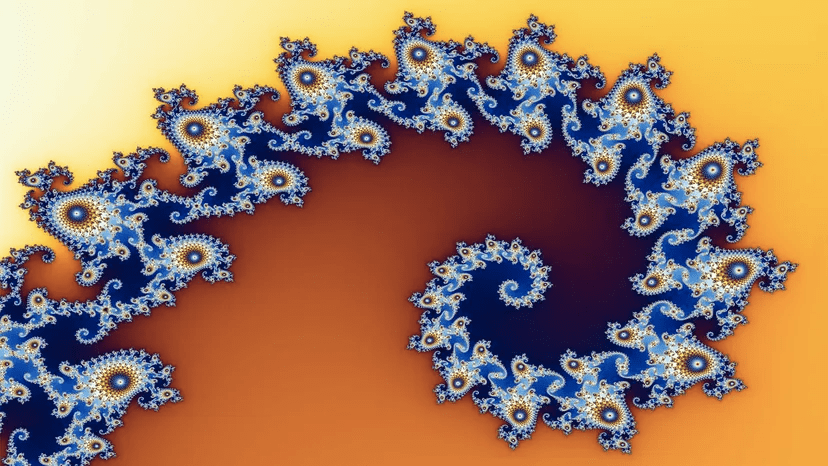

Today, I’d like to share a quote about fractals. We often live in patterns: The small mirrors the large. Likewise, the small can shape and change the large. If we want to change big things, we can start small and let our largest values show up in our small, day-to-day interactions, especially through our relationships. If we want liberation, love, wholeness, and interdependence to be lived on the large scale, we must practice it as lived right where we are in the relationships we have and in our day to day living.

adrienne maree brown says,

“A fractal is a never-ending pattern. Fractals are infinitely complex patterns that are self-similar across different scales. They are created by repeating a simple process over and over in an ongoing feedback loop.

“How we are at the small scale is how we are at the large scale. The patterns of the universe repeat at scale. There is a structural echo that suggests two things: one, that there are shapes and patterns fundamental to our universe, and two, that what we practice at a small scale can reverberate to the largest scale…

“This awareness led me to look at organizations more critically. So many of our organizations working for social change are structured in ways that reflect the status quo. We have singular charismatic leaders, top down structures, money-driven programs, destructive methods of engaging conflict, unsustainable work cultures, and little to no impact on the issues at hand. This makes sense; it’s in the water we’re swimming in. But it creates patterns. Some of the patterns I’ve seen that start small and then become movement wide are:

— Burn out. Overwork, underpay, unrealistic expectations.

— Organizational and movement splitting.

— Personal drama disrupting movements.

— Mission drift, specifically in the direction of money.

— Stagnation — an inability to make decisions.

“These patterns emerge at the local, regional, state, national, and global level — basically wherever two or more social change agents are gathered. There’s so much awareness around it, and some beautiful work happening to shift organizational cultures. And this may be the most important element to understand — that what we practice at the small scale sets the patterns for the whole system.

“Grace [Lee Boggs] articulated it in what might be the most-used quote of my life: “Transform yourself to transform the world.” This doesn’t mean to get lost in the self, but rather to see our own lives and work and relationships as a front line, a first place where we can practice justice, liberation, and alignment with each other and the planet.”

-adrienne maree brown, Emergent Strategy: Shaping Change, Changing Worlds, pages 51-53

* If you’d like to read the book, you can find it here:

https://www.akpress.org/emergentstrategy.html

I’ve watched many a documentary on Netflix, and while I tend to be a sentimental person overall, I don’t particularly like total cheeseball films. That is, unless I’m laughing at them. But even in those moments, I just chuckle a bit, close our eyes, and make a different selection.

But I watched a total cheeseball film in its entirety. I cannot overstate how exceedingly goofy it was in its presentation, but I watched all of it because it told an incredible story about dedicated scientists and innumerable monarch butterflies.

Flight of the Butterflies documents the lives of Fred and Nora Urquhart who spent 38 years working to discover the full migration patterns of monarch butterflies. From 1937 to 1975, they combined small-scale, detailed tracking with a large-scale movement of their own creation. They used self-adhesive stickers to tag the wings of individual monarch butterflies and recruited hundreds of citizen scientists to tag and record their sightings also. The Urquharts wanted to learn where these butterflies traveled over time, and many people in the U.S. joined them in these efforts.

Collectively, they all discovered several distinct migration routes, and for a long while, the Urquharts assumed that the butterflies converged somewhere in Texas. They took trips to Texas where they searched to no avail. Eventually, they began to wonder if Mexico was the destination.

In 1975, that became clearer. Kenneth Brugger and Catalina Trail, associates of the Urquharts, hiked to the winter sanctuary of monarch butterflies. This sanctuary exists on a mountain in Michoacán, Mexico. Mexicans had known about this location for years, but they did not know how far the butterflies had traveled. Adding their knowledge together, the migration patterns became known.[1]

When Brugger and Trail arrived in this location, they were stunned at what they saw. Somewhere between 60 million and 1 billion butterflies. . . on one particular mountain. At any time, this would be an incredible sight to see. But this discovery was additionally long awaited; it was long-hoped and long-dreamed.

In the next year, the Uruqharts traveled to the mountaintop and saw this incredible sight with their own eyes. I can hardly imagine what a culmination experience that would be. Day by day on the small-scale, they worked for an unseen conclusion that was decades in the making. Now they were seeing this massive winter sanctuary with their own eyes, knowing that along with others, their work had helped to map the full migration patterns of these butterflies .

It makes me wonder, do we carry any large-scale hopes? Are we captivated so deeply by anything that we would live and work in its direction daily for decades, even if we never saw the end result? Are will willing to work collectively with others? Will our lives have greater meaning if there is an ultimate goal or purpose before them?

[1] Though Mexicans knew about this incredible location, they were dismissed in the reporting on these events. For forty years, people have used language to say that Brugger, Trail, and the Urquharts “discovered” where these butterflies go. They certainly went on a journey to learn for themselves, and I admire that journey. But they could not have done so without the local citizens.