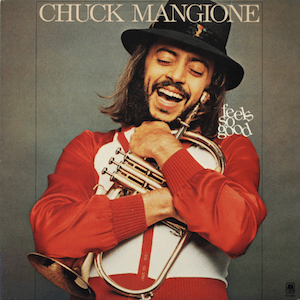

A memory from my childhood which is still so soothing and fun to watch. Also, I like how he pronounces crayons.

I’ll Remind You

All feelings are valid.

All emotions are worthy of being felt and processed.

Every person — (you!) — gets to be complex, whole, off-kilter, centered, and back and forth.

It’s all worth it. You’re all worth it.

But

And

No person — no leader, no neighbor, no partner, no employer, no crafter-of-things-as-they-currently-are — gets to steal your joy and your wisdom of things-as-they-should-be.

Your things-as-they-could-be.

Your things-as-you-make-them.

—Renee Roederer

Mark Carney’s Speech at Davos

On Tuesday, Mark Carney, Prime Minister of Canada, delivered a prescient and powerhouse speech at the Davos World Economic Forum, which brought world leaders to an immediate standing ovation. I was deeply moved by what he shared. I also shuddered at its implications, knowing that despite all our national blustering, our weak-and-getting-weaker U.S. fortress may quickly become more isolated and economically squeezed out.

Still, I believe he speaks truth about where we are. And if we want to right the ship at home as best we can, we, too, can take our sign out of the window. We can start building a better world of cooperation.

Prime Minister Carney starts in French. His English remarks start at 1:17.

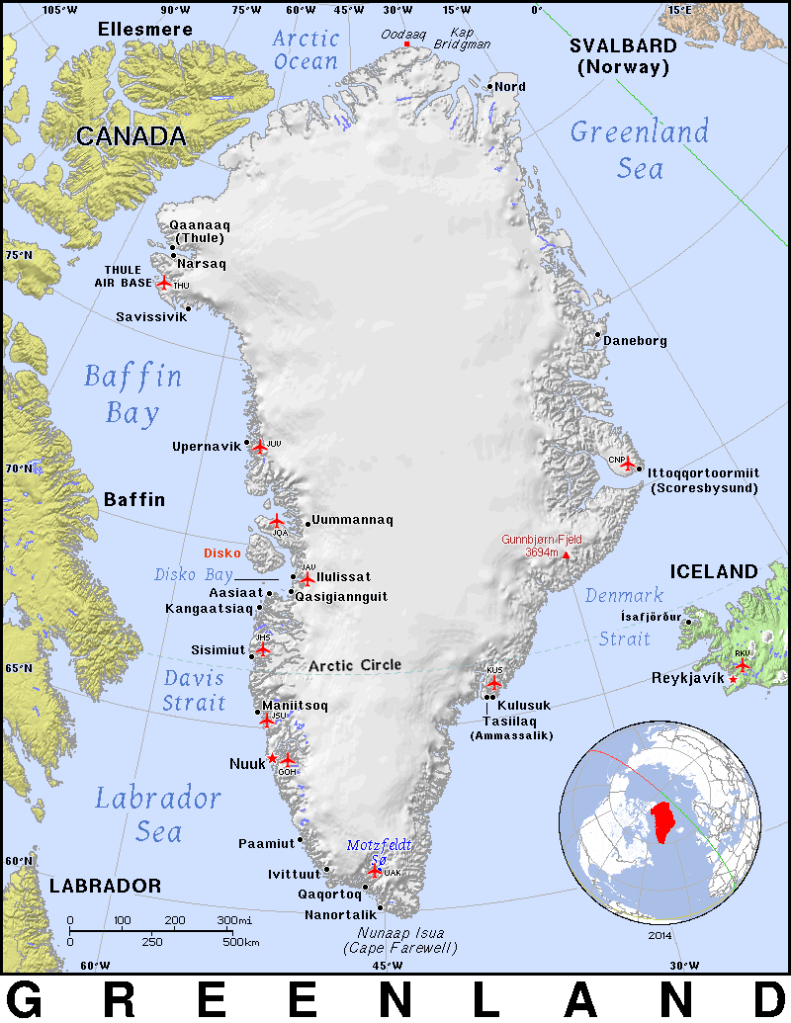

Greenland: Our Collective No

In an interview with the New York Times, Donald Trump spoke with reporters David Sanger and Katie Rogers for hours. At one point, they discussed Greenland. Here is part of that exchange.

“Why is ownership important here?” Sanger asked.

“Because that’s what I feel is psychologically needed for success,” Trump answered. “I think that ownership gives you a thing that you can’t do, whether you’re talking about a lease or a treaty. Ownership gives you things and elements that you can’t get from just signing a document, that you can have a base.”

Katie Rogers followed up: “Psychologically important to you or to the United States?”

“Psychologically important for me,” Trump replied. “Now, maybe another president would feel differently, but so far I’ve been right about everything.”

Psychologically important for me.

How bonkers is it that we are on the precipice of global conflict — if not a full-blown world war — and on the edge of serious economic instability — if not a massive trade war or the devaluation of the dollar — because an insecure man who believes himself all-powerful insists that owning Greenland is psychologically important to him?

This is precisely the moment that calls for a Collective No.

A no from Greenland.

A no from Europe.

A no from the U.S. Congress.

A no from world leaders.

A no from the American people.

How can we allow a delusion this inane to generate so much violence, threat, and instability in the world?

It is truly bonkers.

How did we get here? And where else is our Collective No needed?

Of course, there are many answers to the question that people have been asking repeatedly for years, and lots of people have been saying some version of a Collective No for more than a decade. But I’m also asking myself another question, too. Apart from the person currently holding this delusion, how did we invest so much power in a single office that any one individual could credibly put the world in this position?

That also needs our Collective No.

Let Your ‘No’ Empower Your ‘Yes’

“Let your yes be yes and your no be no.” [1]

This is good advice spoken by Jesus in the Sermon on the Mount. In its original context, there is wisdom about avoiding oaths we don’t truly intend to keep — promises that overreach what we will actually do.

This is also good wisdom for the days we are living now.

Let your yes be yes, and let your no be no. And perhaps we can add this: let your no-s affirm and empower your best yes-es.

There are times when we have to say no to things that would genuinely be valuable to do. Not because they don’t matter, but because saying yes to them would mean we no longer have the energy, commitment, or capacity to say yes to the things we can do uniquely.

In the era we’re living in, we can’t do it all.

We can stay informed.

We can support people who are involved in areas where we are not able to be as active.

We can send our money in those directions.

We can offer encouragement.

And when we are asked for help, we can respond meaningfully and with care and action.

But there will also be things we simply cannot engage as deeply in because we need to carve out necessary space for the work, the roles, and the commitments we are best positioned to hold. That positioning comes from our talents, our skills, and the communities to whom we are connected.

I am deeply grateful for people who are working in areas where I am not able to be as active. I can support them. Likewise, there are needs and communities to which I can be especially present. I need the support of others as I do that.

So let your yes be yes.

Let your no be no.

And let your no-s affirm and empower your best yes-es.

—Renee Roederer

[1] Matthew 5:37

A Good Question

One year ago, after the inauguration, we began to experience an onslaught of executive orders and threats — making sweeping changes, canceling grants, and negating existing rules. It was remarkably overwhelming. Steve Bannon later said the strategy was deliberate, naming it “flooding the zone.”

One year later, it feels like the zone is being flooded again, but this time on the world stage. It’s not one major crisis or a single impending set of threats. It’s Venezuela. It’s Minnesota. It’s Iran. It’s Greenland. The sheer volume makes it hard to know where to look or how to respond.

In the midst of this, I want to share something Eli McCann recently offered. As a gifted humorist and storyteller, he’s a TikToker with a large following. He shared something his Mom used to tell him growing up.

When so many waves of chaos, impending threats, and massive change hit at once, it is completely understandable to feel panicked or despairing. When those feelings show up, we can care for them within ourselves and alongside others. But ultimately, as Eli McCann shared, his Mom would tell him that staying in panic or despair isn’t productive.

Instead, she encouraged him to ask himself a question: What is something I can do today, in my own sphere of influence, that will make the world better? What is something I can actually do?

It’s a simple question. And I also think it’s remarkably helpful. It’s easy to look in all directions and either feel overwhelmed or believe we’re powerless. But we are not powerless.

What can each of us do, right now, in our own sphere of influence, to care well for what’s unfolding — and to help build collective change? Sometimes that question is where steadiness begins.

—Renee Roederer

This Week in Nature

Axolotls!

First Snow Day

We’ve had snow this season, but yesterday was the first day things were actually canceled. It was a snow day for schools, and when that happens in the district where my work office is located, we’re work from home. I really enjoyed that yesterday.

When I was growing up, snow days unfolded differently. We had to wait and watch the news to find out whether our school district would be closed. You’d tune in and stare at a scrolling list of district names, holding your breath, hoping that yours would finally appear.

In the region where I grew up, the same song always played during that scrolling list: Chuck Mangione’s Bellavia. Every single time.

To this day, whenever I hear that song — and let’s be honest, now I usually have to look it up because it’s not exactly playing on the news anymore — I’m instantly filled with childhood joy. There’s something about it that takes me right back to that feeling of anticipation, possibility, and elation.

Last night, I put it on and danced around my house.

Some memories don’t fade. They just wait patiently for the right moment — like the first snow day.

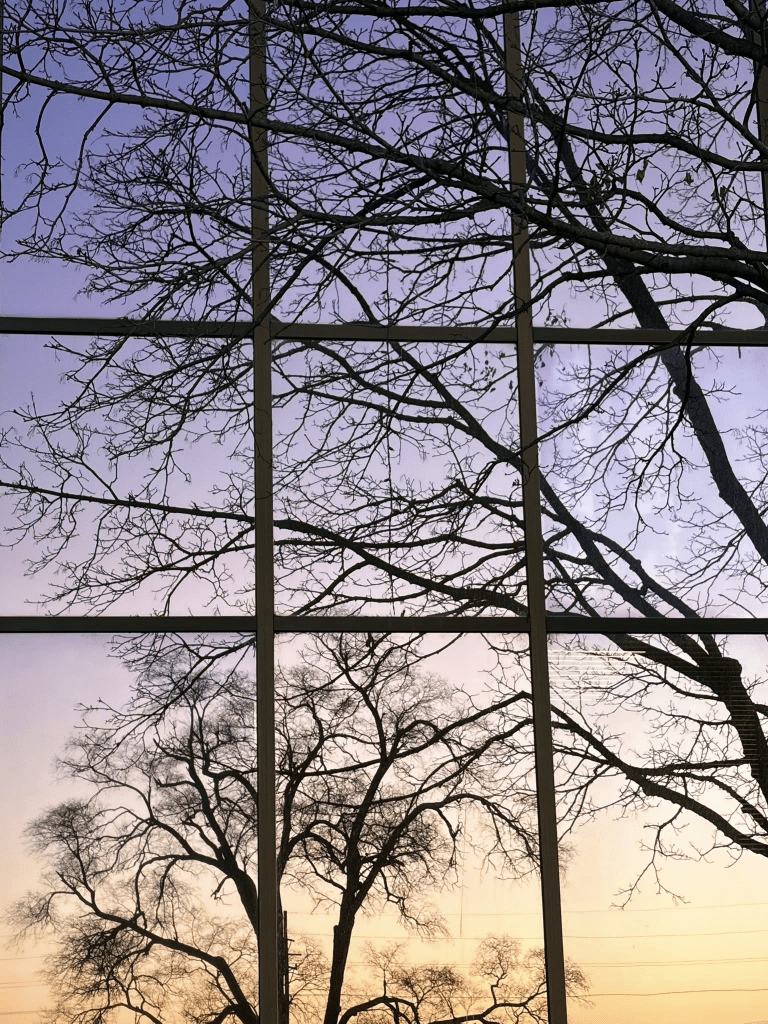

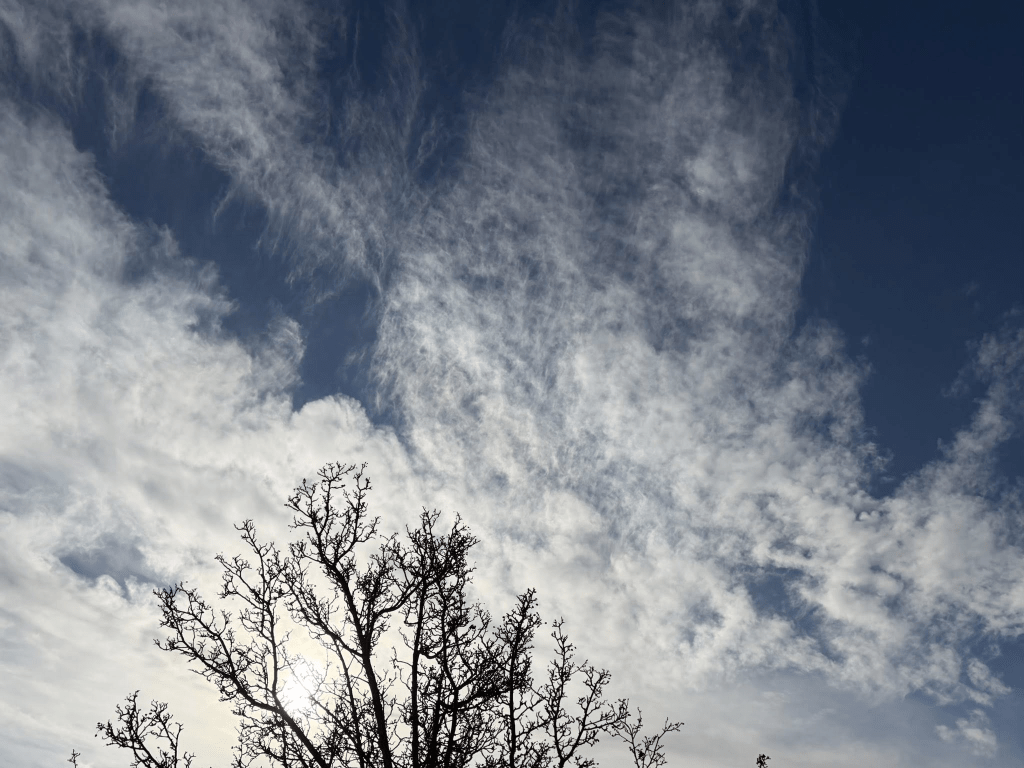

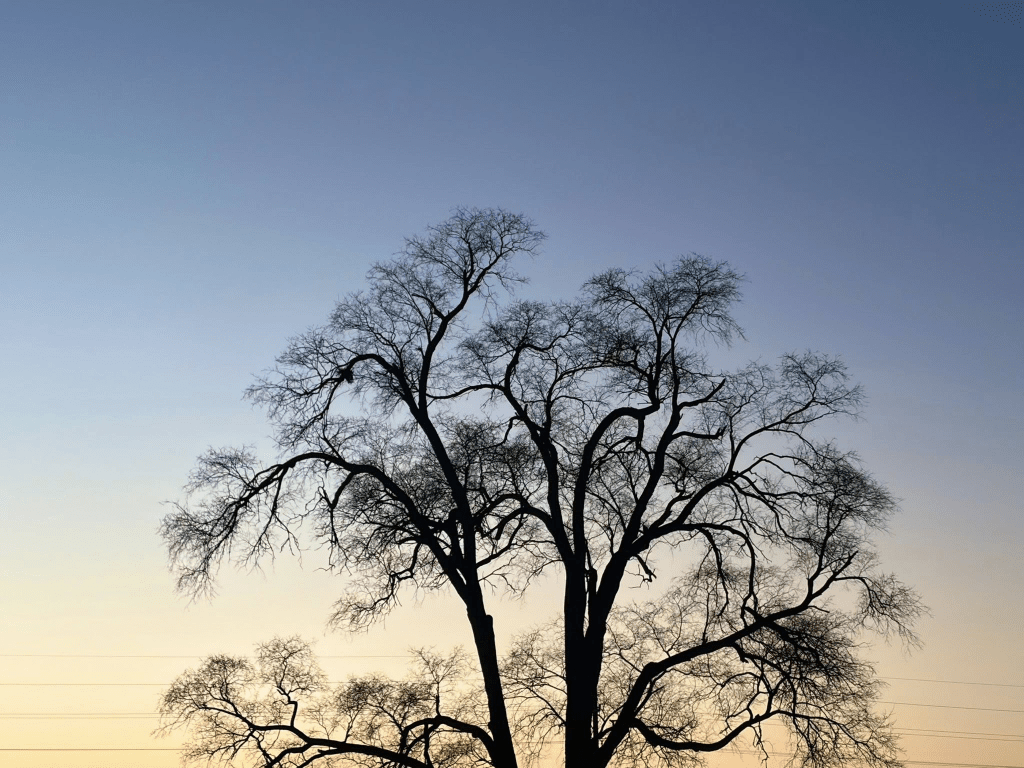

Hidden and Present, Unchanging and Constantly Changing

Once a month, I have the great privilege of co-leading a program called Mindfulness Moments with Andrea Thomas, MA, LLP, a psychologist at Henry Ford Comprehensive Epilepsy Center. What we do together is very simple, yet also surprisingly expansive.

We invite people to arrive on a Zoom screen, something that has become totally routine. And for twenty minutes, Andrea leads us through a mindfulness reflection. We close our eyes, listen, and imagine. Then for ten minutes, I guide us in conversation. Just 30 minutes, once a month.

But when people become present and allow imagination to open, what emerges is often deeply moving.

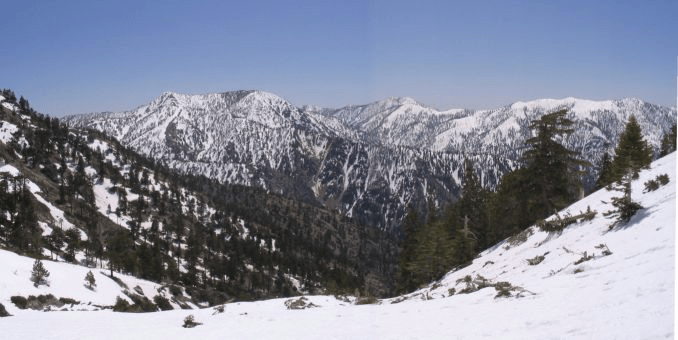

At our most recent gathering, Andrea invited us to imagine a mountain. It could be one we’ve seen or visited before, or one entirely of our own making.

During the reflection, she asked us to notice everything that changes across a year. Animals move and scatter. Plants grow. Snow falls, then melts. Rocks break off. Fog comes in so thick that sometimes you wouldn’t even know a mountain was there at all.

And yet, the mountain remains.

Even when it can’t be seen, it is present.

It is changing all the time, and yet it is also steady, essentially unmoving, save for the tiniest, most imperceptible shifts of tectonic plates over time.

There are moments when people are like that, too.

Sometimes we are hidden.

Sometimes we are visible.

The core of ourselves is solid and unchanging.

And paradoxically, we are also always changing.

When I lived in Pasadena, California, I had a beautiful view of the San Gabriel Mountains. Every so often, fog would settle in so completely that if you didn’t already know the mountains were there, you’d have no idea of their presence. Then the fog would lift, and there they were again. Most of the time, they appeared gray-brown. Occasionally, they were capped with snow.

Unmistakably the same mountains.

Always revealing something new.

I find myself returning to that image.

I invite us to consider the parts of ourselves that are hidden, and the parts that are visible. I invite us to connect with the parts that remain steady, and the ways we are being shaped and changed right now.

And I want to leave you with a short poem, written anonymously by a Jewish person during World War II. It was found in the cellar of a concentration camp. It reads:

I believe in the sun, even when it is not shining.

I believe in love, even when I can’t feel it.

I believe in God, even when He is silent.

Perhaps one of these lines will resonate with us.

Maybe among the parts of us that are hidden or present,

or the parts that are unchanging and yet constantly changing.

—Renee Roederer